In nature, everything is intertwined, related and reliant on the other. It’s an ecosystem. Still, most wouldn’t expect unchecked, hungry deer herds to affect everything from invasive plant species to how things sound in the woods. But it's true.

1. Altered Soundscape

According to Megan Gall, an ecologist at Vassar College who studies how the environment shapes animals' senses, the combination of a surging deer population and the overgrazing of bushes, small trees and leafy plants, is likely changing the acoustics of forests in the Northeast.

"The deer are very, very over abundant,” Gall told National Public Radio in a recent recording of Weekend Edition Saturday. "It's much lusher when there are fewer deer around, and so that's a big change in the structure of the environment."

Less vegetation changes how sound like bird calls is transmitted. Already, it’s known that sounds travels differently through open fields verses forestland. In Gall’s study, which is narrowly focused on how overgrazing affects soundscapes, she relied on fencing to create two contrasting environments. In one area, deer were kept out, leaving a lush understory or layer of vegetation under the main canopy of trees. In another area, deer had access and were free to graze, leaving an understory that had been thinned from foraging.

Each area was surrounded by audio equipment and researches documented how sound traveled differently in each area. The results, according to the NPR report, showed that the overall loudness didn't change much, “but the structure of a sound changed a lot when it was propagated through a lush, green understory that the deer hadn't snacked on.”

As one might expect, the sounds were clearer in the area where deer had browsed. Conversely, sounds in the area with abundant understory bounced off of leafy plants and other vegetation and was less clear.

Researchers believe this could change the calls birds make as they adapt to evolving acoustics. From a deer hunter’s perspective, more stealth is best in overgrazed areas with high numbers of deer. These environments underline the importance of, for instance, avoiding the crunch of dry leaves underfoot.

In areas where hunting is common, particularly in rural regions of the Eastern U.S., deer populations are often kept in check. But in many areas of the U.S., there are not enough hunters to get the job done. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) has reported that about 4 percent of Americans, 16 years old and older, hunt. That's half of what it was 50 years ago and the decline is expected to accelerate over the next decade.

If you look at the northeastern region of the U.S. specifically, where the soundscape study took place, there are even less hunters at about 2.5 percent of the population. Only 2 percent of the population considers themselves hunters in the New England states, while hunters represent 3 percent of the population in the remaining northeastern states or, as classified by the USFWS in its study, the Middle Atlantic states.

Conversely, the East South Central states (Kentucky, Tennessee, Mississippi and Alabama) have a hunter-participation rate of 8 percent; while the West North Central region (North Dakota, South Dakota, Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota, Iowa and Missouri) are also at 8 percent.

2.Lyme Disease 'Spikes Hard'

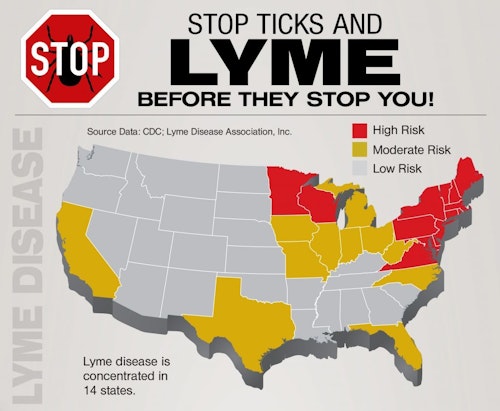

This isn’t the first time the Northeast has been cited as a region negatively affected by dwindling hunter numbers and, as a result, an overabundance of deer. In studies and reports covering the rising number of people infected with Lyme Disease, deer shoulder some of the responsibility. In a new article published in the open-access Journal of Integrated Pest Management, Sam Telford, Ph.D., from the Department of Infectious Disease and Global Health at the Tufts University Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, argues that reducing deer populations is a key component of managing tick populations, according to EntomologyToday.org.

Entomology Today cites other studies to substantiate the theory including, “one study found that reducing deer populations in a community led to a 76 percent reduction in tick abundance and 80 percent reduction in resident-reported cases of Lyme disease.” And according to a Grand View Outdoors article, Lyme Disease: The Hunter’s Disease, Lyme has been reported in 47 states with over 75 percent of all cases in the Northeast region of the United States.

Thermacell, a company known for its mosquito repellents introduced Tick Control Tubes in 2017 to help solve the growing Lyme disease problem. At the time the tubes were introduced, The New York Post said that spring marked “the brink of an epic Lyme Disease Outbreak,” while the New Scientist reported that Lyme was “set to explode.” And Shape Magazine headlined its news story with, “Lyme Disease Is About to Spike Hard This Summer.”

When it comes to disease of any kind, “spiking hard” is not what you want. And the Lyme epidemic in the northeast hasn’t subsided since the flurry of stories cycled through the news nearly two years ago.

Cathain Pratt, who identifies herself as an avid gardener living in Connecticut, says, “all my children have had Lyme disease. This past spring, I found a tick on me almost every time I was outin the garden,” she writes in a Tick Tube review she posted to Amazon. Many of the reviews for this product were posted by customers from the Northeast where hunter numbers are the lowest and deer density tends to be higher.

3. Invasive Plant Species Thrive

A third factor influenced by unchecked deer herds is invasive plant species. one might assume that hungry deer might at least mow through these unwanted and often dominating plant species and may some sort of positive contribution in light of the bleak affect they’ve had on Lyme disease. Not so. Instead, deer have as little use for these plants as humans do. In fact, they find invasive plants unappetizing. And by rejecting invasive plant species, deer inadvertently promote their success.

The silver lining, perhaps, is that little does more to demonstrate the benefits of hunting than unchecked animals wreaking havoc on other species and throwing off a well balanced ecosystem. The Smithsonian Insider reports, "The eating preferences of the hordes of whitetail deer now living in the eastern United States is gradually altering the traditional composition of plant species in its forests, lowering the diversity of native plants while giving a boost to invasive populations."

Whitetail deer are native to the Eastern U.S. And because of this, they are interdependent on their natural habitat and they rely on the plants indigenous to this habitat. Naturally, as the basics of ecology go, they're not likely to seek out invasive plants for sustenance. These plant species are not indigenous to their natural habitat.

(Disclaimer: Japanese honeysuckle is abundant in a large part of whitetail country. Although it is a non-native, invasive plant, it is high in protein and a valuable mid-winter food source for deer.)

Once the natural balance is disrupted, a string of actions and reactions are set into motion and this changes forest plant ecology. So take for instance other native animals reliant on the same forest ecology. With native plants being elbowed out by thriving invasive plants and deer populations dominating the food sources available, other animals like wild turkeys can suffer.

These events can also have long-term impacts on forest regeneration including stressors to native oak trees.