Wildlife biologists in southwestern Wisconsin know what to expect when investigating reports of sick deer on farms, marshes and woodlots. They even have a name for them.

“We call them Droolers and Shakers,” said Don Bates, former supervisor of chronic wasting disease operations for the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. Bates, now retired, said many people ignore CWD because most infected deer die alone and unseen. Although some huddle against a garage or near a dryer vent in winter to protect themselves from the cold, most die unseen and undocumented in thickets, wetlands or river bottoms.

“If CWD wasn’t such an insidious unseen killer — if it had teeth, claws and hair — the hunting public would be outraged by it,” Bates said. “They want the problem to go away. They’re not talking about it. They’re in denial, but it’s not going away. It’s getting worse at faster and higher rates than ever.”

CWD is an always-fatal brain disease. Once deer contract it, their life expectancy is about 18 to 20 months. They typically look healthy the first 16 months before showing its effects. Those signs include tremors, heavy drool, staggering and stark ribs and spinal bones outlined beneath a ratty hide. In advanced stages, they lose their fear of humans.

Before the 2000s, CWD was considered a “Western” disease because it appeared to be confined to the Wyoming and Colorado region. Mule deer were the most common victims, although elk weren’t immune. In February 2002, however, Wisconsin found its first CWD cases while testing whitetails killed in November 2001 southwest of Madison, the state capital. Soon after, Illinois found its first cases near the Wisconsin border.

The disease had jumped the Mississippi River and was headed east. New York and West Virginia found their first cases of CWD in 2005. Those initial discoveries east of the mighty river caused alarm. Roughly 10 percent of Wisconsin’s deer hunters didn’t buy a license in 2002, and wives and mothers closed their kitchens to venison when learning CWD was related to mad cow disease, which had killed Europeans eating infected beef.

Then most people calmed down from 2005 through 2010 when no one died from eating venison, and CWD apparently leveled off at low rates. And when disease experts in Wisconsin documented escalating CWD rates in some areas in 2009, few hunters noticed.

Disease Rates Spike

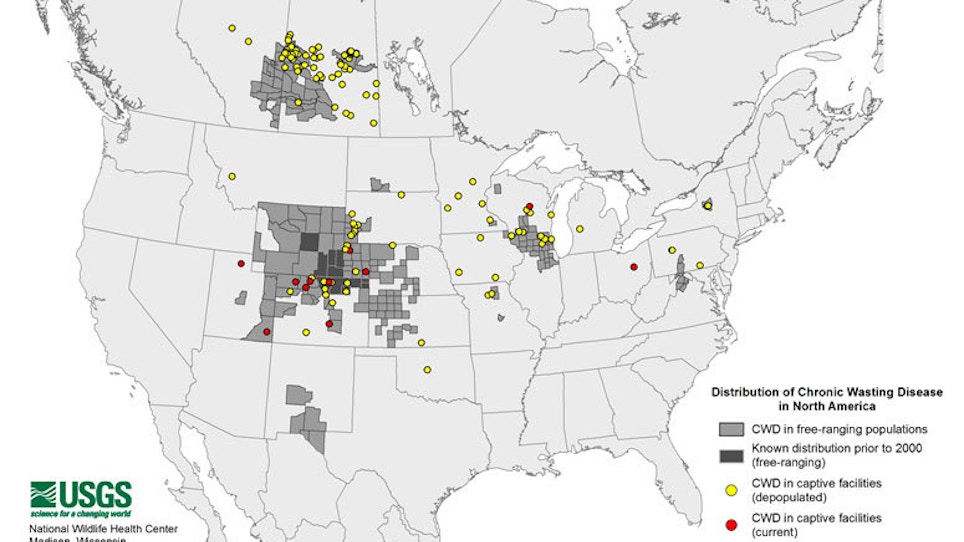

But if current CWD trends continue nationwide, those carefree days are ending. As of April 2015, CWD has been found in wild deer in Texas, Utah, Colorado, Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, South Dakota, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Wisconsin and Wyoming, as well as Alberta and Saskatchewan. It has also been found in fenced game farms in most of those states and provinces, as well as Michigan, Montana, Ohio and Oklahoma.

Eastern states hardest hit are West Virginia, with nearly 175 positive cases; Illinois, with nearly 410; and Wisconsin, with nearly 2,840. In fact, every state bordering Wisconsin, except Michigan (the Upper Peninsula), has found at least one CWD-infected wild deer. Wisconsin has also reduced CWD testing, and since 2013 it has adapted a “passive approach” to the disease. It now merely monitors for the disease instead of trying to control it.

If test results from the Dairy State’s 2014 hunting seasons mean anything, the passive approach is making things worse. Despite sampling the second-lowest number of deer in Wisconsin’s 14-year monitoring program, the DNR documented a record 6.1 percent disease rate in 2014. In real numbers, 329 of 5,414 tested whitetails had CWD.

That marked the third straight year Wisconsin’s CWD rate exceeded 5 percent of tested deer, as well as the third straight year that sick deer exceeded 325. That might sound like mere statistics to some, but not to Matt Limmex, a dairy farmer who has spent his life on the family’s property west of Madison. During 2012, 11 sick deer were killed on Limmex’s lands, six during gun season. Limmex shot the other five at the DNR’s request after noticing them near his farmyard. Three were so sick they couldn’t flee when Limmex approached.

Limmex’s farm is located in the “Wyoming Valley” of north-central Iowa County. In recent tests, this area’s CWD rate hit a record 40 percent and 22 percent for adult bucks and does (2½ years and older), respectively. Further, CWD rates in yearling bucks and does were 18 percent and 15 percent, respectively. Just east of there, the disease rates are 27 percent for adult bucks, over 12 percent for adult females, and 8 percent and 7 percent, respectively, for 1 1/2-year-old males and females.

West Virginia is also documenting worrisome trends. In 2006, its Division of Natural Resources reported all CWD cases were within a 15-square-mile area. The infected area grew to 25 square miles in 2007, 32 in 2008, 49 in 2009, 61 in 2010, 73 in 2011, 85 in 2012, and 108 in 2013.

Meanwhile, this “Western” disease was worsening out West. By 2010, CWD experts declared the South Converse mule deer herd in southeastern Wyoming the world’s sickest herd. That year, 48 percent of its hunter-killed deer carried CWD. At the same time, muley numbers fell 50 percent, even without antlerless harvests. By 2011 the herd was 56 percent below the 7,000 goal and still dropping.

Once A Crisis, Now A Yawn

The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources dispatched this 3 1/2-year-old buck after it was ravaged by chronic wasting disease in September 2012.

Such numbers suggest CWD is no longer a “political disease” that would forever hover near 2 percent infection rates, as skeptics often repeated. But skeptics weren’t the only ones who ignored CWD while it quietly spread. In 2002, for example, the U.S. Department of Agriculture declared CWD a crisis, enacted importation guidelines for hunter-killed deer, elk and moose from Canada, and helped states monitor the disease.

But by 2012, the USDA’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service stated CWD no longer needed nationwide attention. In explaining its $14 million cuts for CWD monitoring, APHIS wrote: “Since these are local or regional disease spread issues, state and local governments should assume a more active role, and better anticipate and plan for future needs.”

Likewise, state and federal money for CWD research dried up. By 2013, as Professor Michael Samuel at the University of Wisconsin-Madison concluded a round of CWD studies, he expressed little hope of finding money to study why CWD is now increasing so fast just 30 miles west of his office.

“It’s disturbing, but CWD research is on the way out,” Samuel said. “We could generate hypotheses and proposals to study what’s behind the jump, but I doubt we’d get the funding. There’s little interest in CWD these days, both in Wisconsin and nationwide.”

Still, some research has continued. In late 2014, a Colorado State University study reported an experimental vaccine partially prevented CWD. Of 11 deer exposed to CWD, five were treated with varying doses of the vaccine, and six received placebos. Within two years, the six deer receiving placebos were infected, and they lived about another 20 months. Meanwhile, of the five receiving a vaccine, the one receiving the highest dose was still alive in late 2014, while the treated deer survived an average of 30 months. About the same time these findings were released, the Canadian government invested $1.6 million in a vaccine study at Pan-Provincial Vaccine Enterprise in Saskatchewan.

Although vaccines might eventually slow CWD, few expect they will remove it from the landscape, especially if scientists can’t find ways to reliably administer vaccines to free-ranging deer. David Clausen, a retired veterinarian and former member of the Wisconsin Natural Resources Board, also worries that hunters will become even more complacent about CWD if they think a “magic bullet” is within reach.

“Now is not the time to let deer herds keep growing in CWD areas,” Clausen said. “CWD costs will always be lowest in the smallest areas with the fewest deer possible. The more deer you have, the more expensive and troublesome it will be to vaccinate them, should that possibility ever occur. It’s one thing to control a disease inside a pen; it’s quite another to do it in the wild.”

Clausen also worries that prolonging the lives of CWD-infected deer could have unintended costs. “The longer a sick deer lives, the more it infects its environment,” he said. “We have to realize that diseases don’t give up easily.”

Shoot For The Future?

But drugs might not be the only remedy. Professor Samuel said a study by one of his graduate students, Christopher Jennelle, now a Ph.D., found that if hunters aggressively harvest bucks, they’d likely slow or pause CWD’s growth. That’s because mature bucks tend to be infected at twice the rate of adult does. Jennelle’s study projected that a buck-focused harvest plan would soon start reducing CWD and drop it to about a 5 percent infection rate in 30 to 40 years.

“We’ll probably never get rid of CWD, so the goal becomes how to get it to a manageable level, one that doesn’t impact our deer herd, and how do we try to contain it so not every area gets infected?” Samuel said. “If we don’t, the disease will grow worse, and before long have impacts on the deer population.”

Jennelle’s research article put it this way: “The trade-off between strategies is clear. CWD can eventually be reduced with fewer opportunities to harvest healthy bucks, or more adult bucks may be available for harvest but with higher rates of CWD infection.”

However, the second scenario doesn’t guarantee more adult bucks. Samuel said as CWD worsens, fewer bucks will reach older age classes, and hunters who manage their properties for bigger bucks will start losing more of them to CWD.

“These are sobering options, but the sooner we act, the less severe the problems and choices we’ll face,” Samuel said. “If we don’t do anything and just stick with what we’re now doing, we’ll lose more adult males because we’ll get such high infection rates. Most of those deer will get killed, one way or another.”

Meanwhile, Samuel said the research reinforces his skepticism that evolution and natural selection will ever provide management options, as some deer hunters claim.

“The sooner we actually do something about CWD, the better off we’ll be,” Samuel said.