Photo: Yevhenii Dorofieiev (iStock)

This question may come to mind in the springtime when many sportsmen are choosing between the woods and hot, strutting gobblers or top water and spawning bass and bluegill.

Hunting turkeys by boat takes on a whole new meaning if you’re also fishing while you’re on the water. Is this safe? And who loads the boat with fishing rods and a shotgun to serve the two goals in mind? But there’s someone who claims to have landed a stringer full of blugills before pointing his canoe toward the bank where he collected a dead gobbler, he’d shot as he saw the bird crossing the pond dam.

But, if the intent was to fish (which he said it was), why did he have the shotgun in the boat at all? He never said. Maybe he made the whole thing up. It’s unknown. But this writer has always been a wild card, which makes sense — sort of — because he was kicked in the face by an angry horse who didn’t appreciate the horseshoe that was being nailed to its hoof.

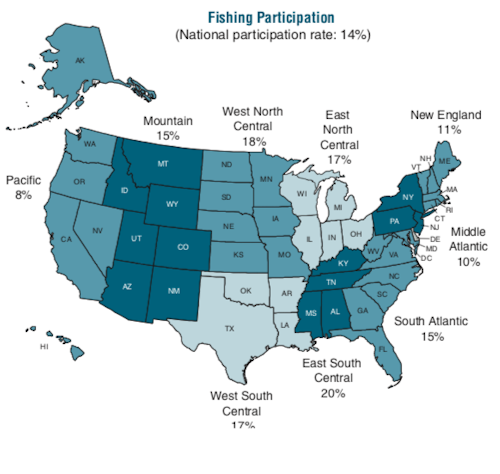

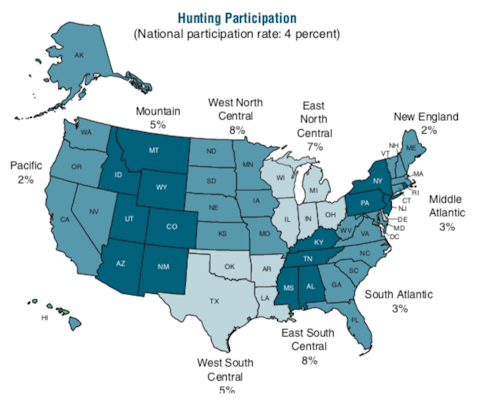

Most anyone who enjoys hunting and fishing feels the conflict springtime when spawning fish and breeding wild turkeys make things interesting for sportsmen all at once, after a winter of nothingness. How many are there out there — sportsmen who consider themselves both anglers and hunters? In the U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s most recent survey, 67 percent of hunters said they also fish, but only 21 percent of anglers also hunt. These percentages translate to nearly 7.7 million Americans who said they fished and hunted in 2016, while 35.8 million said they only fished and 11.5 million only hunted. Interestingly, the survey reported that a quarter of all wildlife watchers either hunted or fished or participated in both activities.

Types of Fishing Favored by Hunters

While the U.S. Fish and Wildlife’s survey didn’t poll hunters who also fish on the type of fishing they prefer, fishing data tells the story. Anglers, including those who hunt and fish, overwhelming fished freshwater. A preference, one can assume, is largely driven by the bodies of water most Americans have access to.

Much like deer as the most hunted species by U.S. hunters, black bass — which includes the species Smallmouth and Largemouth bass — is the most sought after fish among all fish despite the popularity of panfish and trout and catfish. There are 29.5 million freshwater angers in the U.S. (excluding those anglers fishing the Great Lakes for walleye, salmon and steelhead) and of those, 9.6 million are bass anglers, 8.4 million fish for panfish and 7.8 million pursue trout. Among all saltwater anglers, most spend their time pursuing red drum or redfish.

The Popularity of Fishing vs. Hunting

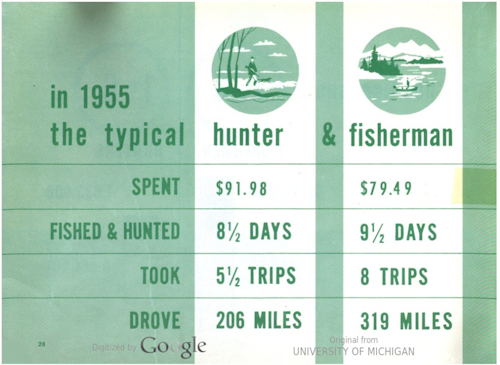

It’s true that anglers have historically outnumbered hunters, but the chasm between the two hasn’t always been as wide. Hunter numbers were as high as 14.1 million in 1991 but, if you go back to 1955, when the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service first started doing its hunter and angler survey, the number of hunters has come full circle, down slightly from 11.8 hunters in 1955 to the aforementioned 11.5 million in 2016. Meanwhile, there were a reported 20.8 million anglers in the U.S. in 1955 compared to 39.6 million who said they fished in 2016. In 1955, one in every five men hunted. Of course, just like today, rural areas had a higher percentage of hunters in 1955 than urban and metropolitan areas. The difference is there is far less rural areas in the U.S. today than over half a century ago.

This points to of the primary causes of the decline in U.S. hunting: access. There are approximately 38 million acres of federal public lands in the U.S. that are not accessible to the public because they’re landlocked by privately owned lands. Conversely, other states are dominated by private land. Most of the hunting ground in both Illinois and Texas, two states known for their strong hunting cultures, is tied up in private ownership. Ninety-five percent of Texas is privately owned, while 90 percent of Illinois’ landscape is private property.

“This has led to a number of properties being leased to the highest bidder, often far above the amount the average hunter can afford,” said Andrew Limmer, a National Wild Turkey Federation regional director for Illinois.

However, any one who wants to hunt bad enough can find opportunity and instruction. While advocates for making more public land available to hunters would like to see more options for hunters, every state currently offers public hunting ground. Some state and federal wildlife agencies also offer programs in addition to the standard hunter education curriculum that’s required to obtain a hunting license. In states like Wisconsin and Kentucky, wildlife agencies host educational workshops to assist those who would like to hunt, but don’t know where to start.

In Kentucky, the state’s wildlife agency also offers Field to Fork workshops for Kentucky residents who would like to harvest their own local meat. Its next scheduled workshop is March 23, and it covers everything a new hunter would need to know about hunting spring turkeys in Kentucky from hunting regulations to turkey calling, strategies, breasting out and cooking wild turkey meat. The cost is an affordable $25.

The agency’s website describe the workshop as a “hands on program for those who are unfamiliar with the post-harvest process of deer hunting.” Topics covered include butchering, meat safety, meat canning, cooking, vacuum sealing and grinding. Each hunting workshop is a little different. One might focus on the biology of game animals and the habitats of featured game animals, while another might cover hunting tactics, scouting and field dressing wild game.

According to the Archery Trade Association, these field-to-fork programs are growing in popularity. Wildlife agencies in Georgia and Minnesota are also promoting them, and other states plan to start their own programs soon. These program start-ups are aided by online modules, program planning and administration guidelines and other useful tools found at locavore.guide, an online resource funding by a federal grant from the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Program, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Multistate Conservation Grant Program.