I’m flat on my back, peering out from under the mesh hood of a mud-covered 11-pound Power Hunter layout blind. Jet, my wife’s 9-year-old female black Lab, lies on an old burlap feed sack at my right elbow. Just off our toes, the gray waters of the Columbia River lull against the sand in a sneak-and-retreat manner. And in front of us, three 12-decoy mainlines ride the Columbia’s chop — one upstream and two down, with the outermost rigging run at a 45-degree angle to the little secluded stretch of riverbank I call The Beach. Between the lines, a dozen more bluebill blocks, each individually tethered to the river’s sand bottom, boil atop the water. For the Type A decoy man who can’t stand for his decoys to touch — well, partner, the blob theory of spread design ain’t for him; for me, here, it works just fine.

I’m flat on my back, peering out from under the mesh hood of a mud-covered 11-pound Power Hunter layout blind. Jet, my wife’s 9-year-old female black Lab, lies on an old burlap feed sack at my right elbow. Just off our toes, the gray waters of the Columbia River lull against the sand in a sneak-and-retreat manner. And in front of us, three 12-decoy mainlines ride the Columbia’s chop — one upstream and two down, with the outermost rigging run at a 45-degree angle to the little secluded stretch of riverbank I call The Beach. Between the lines, a dozen more bluebill blocks, each individually tethered to the river’s sand bottom, boil atop the water. For the Type A decoy man who can’t stand for his decoys to touch — well, partner, the blob theory of spread design ain’t for him; for me, here, it works just fine.

“Where they at, Jetter?” I’m talking to the Lab next to me. She hears and, at least I think, understands, and steals a quick look upriver before turning her attention once more to the northerly flow of current. “She knows,” I say out loud to no one in particular. Five minutes pass; then 10, and a short whine escapes my partner. Turning, I see her staring at something I can’t make out. But then on the corner where the Columbia breaks once more to the west, I see them. A black smudge, as if the river itself were on fire, the smoke bobbing and weaving over the surface. But it’s not smoke — it’s the reason we’ve come to Washington, and to the river. Bluebills.

The flock approaches swiftly, the birds all characteristically low to the water. Three hundred yards out, it seems that the mass will pass, uninterested. “Let’s let ’em know we’re here, Jetter,” I whisper as I put the single reed to my lips and let loose with a low-pitched growl. Two birds, then another and another, break from the pack and turn onto a collision course with my small sandy part of the world. As I’d hoped, the quartet follows the outside of the angled mainline and heads for the knotted mass of plastic 25 yards beyond my waders. They would have made it, too, had I not interrupted their flight plan with a full three-round contingent of Xtended Range No. 5s. Four in, and two out — and I’ll blame a pure, unadulterated case of accuracy trauma for not going three-for-three. By the time I put the empty Mossberg down, Jet’s halfway back with the first duck. It’s a wonderful retrieve in classic style on a most traditional bird.

A half-hour later, the scene was repeated — this time, though, it was a six-bird group traveling upriver, with all six boring into the decoys as if mine was the last piece of undisturbed water on the planet. Whereas the first two ’bills were lesser scaup, this was a greater — a strikingly handsome black-and-white brute, with a bull chest and skiffs of cloudy white running out to the tips of his primary feathers. Jet brought him to hand and stood, as she’s prone to do, to drip-dry on my blind bag and all its contents; she got a biscuit anyway. We stayed another hour, me drinking lukewarm coffee and her eating year-old crumbles of Pop-Tarts and granola bars, but the flight had stopped. Breakdown at 9:30 took 20 minutes, maybe 25, and as we pulled out of the two-track sand road, the incoming tide was already starting to erase all evidence that a hunt had even taken place. I couldn’t help but smile. There’d been no boat to trailer, no ramp fees to pay, and no 90-minute decoy spread — just me, the dog, a handful of plastic ’bills, 11 pounds of blind, and the river. And the ducks; let’s not forget them.

Divers and dry ground aren’t often used in the same sentence, and yet here I am talking about gunning bluebills from the confines of a land-based layout blind. Dry-ground divers? The ultimate oxymoron? True, when most waterfowlers think of hunting divers — scaup, redheads, canvasbacks, goldeneyes and others — they’re also thinking of big water, dozens of decoys and a blind, be it a stick-built hide or a modified boat. Puddlers, they’ll say, can and quite often are successfully hunted from terra firma; geese, too. But divers? “You gotta get out where the birds are,” they’ll say with a grin that translates into “What a top-water yahoo.” So you can’t kill divers from dry ground? Well, folks, to borrow a line from The Discovery Channel — that myth is busted!

Location, Location, Location

As is the case in the real-estate world, gunning divers successfully from dry ground is all about location. It’s a broad statement, I agree; however, any blind on any lake or river can be effective given the right situation and under the right conditions. There is one way to increase the odds that you’ll be seated, nice and dry, in a high-traffic area — scouting.

As is the case in the real-estate world, gunning divers successfully from dry ground is all about location. It’s a broad statement, I agree; however, any blind on any lake or river can be effective given the right situation and under the right conditions. There is one way to increase the odds that you’ll be seated, nice and dry, in a high-traffic area — scouting.

Divers aren’t known for flying over large expanses of dry ground, preferring to raft on and trade over open water. However, most bodies of water will feature some geographic condition — points, or the opposite corners at a bay mouth — that allows the land-based gunner to get closer to the birds without ever leaving dry land. The Beach, mentioned earlier, is little more than a nondescript bulge reaching 30 yards out into the Columbia; still, like a pier, it protrudes from a flat (north/south) shoreline, and puts me in a high-visibility position. Farther west where the Columbia meets the Pacific, a quarter-mile-long point separating bay from tributary mouth serves as a traditional diver gunning platform. Both locations feature identical characteristics that make them good choices for a power hunter and three or four strings of bluebills — visibility, shallow water and bird traffic.

How did I find these places? Actually, the birds showed me The Beach; rather, it only took seeing small groups of ’bills rafted just off the sand on several different drive-by occasions for things to click. Then it was simply a matter of plotting as to how to hide, and how to set the decoys. Since then, I’ve discovered other locations, thanks to graphic aids such as Delorme Mapping’s TopoUSA 6.0 topographical software, or Internet sites like Google Earth and TerraServer.com. My process is simple: Find a terrain feature that gets you “offshore,” no matter how insignificant it might seem, and then watch.

Diver Blinds On Terra Firma

Some will disagree, I’m sure, but if you camouflage yourself to match your surroundings, sit still, and keep that white neon light called a face either covered or hidden until you’re ready to take the safety off — well, darn near anything can be a diver blind. Now, that’s not to say that divers don’t get gun-shy — they can, and do — however, given the oft-light pressure they receive, the divers tend to be a mite more trusting than are Arkansas greenheads or southern California pintails.

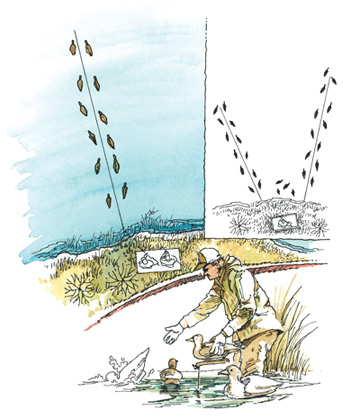

When I think dry-land divers, I think mobility. And here, mobility translates into one of two different styles of blinds — natural, and modern layout blinds. Natural blinds in a diver scenario are self-explanatory; however, it’s important to remember that not all natural blinds require willows, spartina grass, cattails and such vertical cover. A small jumble of driftwood, a washed-up root wad, cobblestones — even small wash-outs or bushel basket-sized clumps of spike rushes can serve well as a natural blind. Again, it goes back to dressing as Ma Nature dictates and, most importantly, practicing movement discipline.

When Avery Outdoors introduced its Power Hunter layout blind in 2002, I immediately put it to use in western Washington as a ground-based diver hide. Lightweight, collapsible and extraordinarily portable, the Power Hunter worked well — and continues to work well — in situations where there was absolutely no natural cover at all, such as is the case at The Beach. Hunting with a partner means I can strap two Power Hunters on my back, while he or she packs a couple dozen life-sized bluebills and a small bag of anchors. We’re self-contained and mobile, and can pick up and move in short order if the birds let us know that’s what we need to do.

Setting The Spread

Setting The Spread

In-depth scouting not only informs you regarding where to hunt, but how to hunt, and this applies both to spread size and the method by which you rig and set those blocks.

Often, my land-based diver shoots are done on a small scale — walk-in, natural blinds or lightweight layouts, bare essentials gear, and as few decoys as I feel I can get away with. Three dozen bluebills work at The Beach; the estuary, due to its size and open-water expanse, requires three or perhaps even four dozen. The type of decoys depends on the means by which they find themselves at the water’s edge. A short or non-existent walk, and I’ll throw Greenhead Gear’s (GHG) over-size bluebills (7 ½ by 15 inches), with perhaps a dozen ’cans or goldeneyes off to the side. The Beach is a prime example here, as I can drive to within 30 yards of where the lines will actually be set. If I’m packing blocks in on my back, however, I’ll turn to GHG’s smaller (12 ½-inch) life-sized bluebills, and cut the size of the spread down to a couple dozen, give or take.

The answer to how my rigs are set is actually two-fold. I use long (main) lines consisting of 90 feet of leaded crab cord (see sidebar for more); anchors, unless it’s rough, are 1 ½-pound grapple weights, available at Cabela’s, upstream and down. A dozen decoys ride the lines, each line equipped with its own dropper and 5-inch stainless-steel gang rig clip. Fashioned from TangleFree cord, the droppers range from 30 to 40 inches — these lengths allow dogs to swim perpendicular to the lines without getting tangled in the main lines, and the varying lengths help stagger the decoys, making them look more natural. At times, I’ll set only long lines; other times, I’ll set the aforementioned blob of individually-rigged ’bills in front of the blind, with long lines to the right and left.

More often than not, I’m setting a land-based diver rig on my feet; that is, I’m wading and rigging, just as I would with puddler decoys. There are times, however, such as on The Beach, where I will use my 10-foot (#53) ATTBAR Aquapod as a miniature tender boat in order to set and retrieve the lines. I’m still hunting from dry ground, only I’m using the ’Pod simply because of water depth and the tides.

Certainly, diving ducks and deep-water scenarios are as traditional as is anything within the waterfowler’s realm; however, there’s just something about gunning black-and-whites, lordly ’cans, and rocketing redheads while lying flat on your back on dry ground. That’s right — dry ground. But don’t worry; it’ll rain, and you’ll be wet enough. After all, this is duck hunting, isn’t it?