The Study

The Study

The study was spearheaded by wildlife consultant Bryan Kinkel on a 488-acre property in west-central Tennessee. The property is best described as a Ridge and Valley system featuring long, narrow, hardwood ridges separated by steep, narrow valleys containing food plots and old fields. The study took place over a 10-year period from the winter of 1995 to the winter of 2004.

The first step of the project involved classifying the habitat into one of several categories. The defining lines between categories were classified as habitat edges. To produce rub sampling areas, long transit lines were randomly placed across the landscape. Rub data were collected by walking each transit line and recording the number of rubs within 10 meters of the transit line. Each rub was classified by the habitat type in which it was located and the distance of the rub to the nearest habitat edge was recorded. All sampling was conducted in late winter after the majority of rubbing had concluded.

It's All About Edge

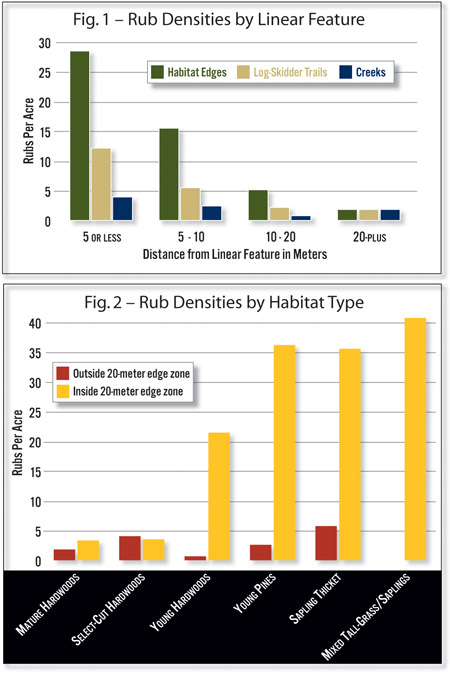

The results of the study revealed strong relationships between habitat edges and rub densities. Kinkel's research revealed that the highest rub densities (27.9 rubs per acre) occurred within a narrow strip within 5 meters of habitat edges. Rub densities declined with distance from habitat edges, with the strips 5 to 10 meters from habitat edges averaging 17.0 rubs per acre and the strips 10 to 20 meters from habitat edges averaging 7.7 rubs per acre. The "edge effect" appeared to end approximately 20 meters from habitat edges, as rub densities averaged 1.8 rubs per acre beyond this distance.

In addition to habitat edges, other linear features such as roads and creeks were analyzed (see Figure 1). Both roads and creeks displayed some "edge effect," but not nearly as strong as habitat edges, with the exception of old, abandoned log-skidder trails. Rub densities averaged 12.4 rubs per acre within 5 meters of these trails and 5.5 rubs per acre within 5 to 10 meters of these trails. The data also suggested that the less a road is used and maintained by people, the more often it is incorporated into a buck's travel patterns.

However, no matter the habitat type, rub densities were much higher within 20 meters of the outer edge of each habitat type or near linear features such as skidder trails. In fact, some habitat types displayed nearly 15-fold increases in rub densities in the 20-meter zone bordering the outer edge of the habitat or paralleling other linear features (see Figure 2). This suggests bucks are using these habitat edges as travel corridors or concentrated activity areas.

Topography and Deer Rubs

Topography and Deer Rubs

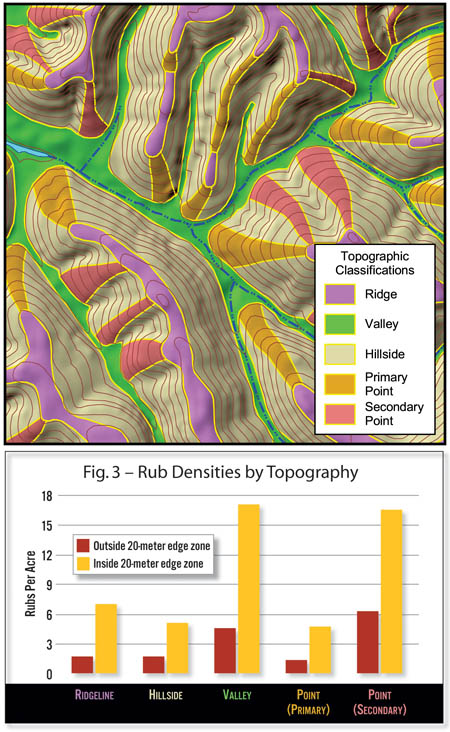

The influence of topography on buck rubbing also was examined. Kinkel and his research team classified the study area into one of five categories: Hillsides, Ridges, Valleys, Primary Points and Secondary Points. The tops of ridgelines and level upland plateau regions were classified as Ridges. Narrow valleys or level bottomland areas were classified as Valleys. The slopes off ridgelines or plateaus to where valleys or bottomlands began were classified as Hillsides. However, two types of slopes received unique classifications. Topographic points that were terminal ends of ridgelines were classified as Primary Points, and small topographic points that descended from the side of a ridgelines or upland plateau areas were classified as Secondary Points (refer to the map on this page).

When the researchers analyzed the relationship between rub densities and topography they found that two terrain features—Valleys and Secondary Points—displayed significantly higher rub densities. Both had rub densities 250 to 300 percent higher than the other three topographic features. While unsure exactly why these features were used so heavily, they discovered a strong correlation between good cover and rub densities associated with valleys. Where valleys contained good cover, rub densities were high. However where valley cover was lacking, such as in open hardwood forests, rub densities were low. In fact, cover habitat located in valleys and bottomlands displayed considerably higher rub densities than the same habitat located on other topographic features. They speculated that the reason Secondary Points were used more for buck rubbing activity likely was due to bucks using these slowly descending points as "ramps" for easy access between valleys and uplands.

When the effects of 20-meter "edge zones" were analyzed for topography, all topographic features displayed large increases in rub densities. The already higher rub densities for Secondary Points and Valleys were increased dramatically when edge zones were present (refer to Figure 3).

Hunting Implications

As bowhunters, you realize that hunting the edges of large food sources such as food plots or stands of oak trees can be frustrating because deer can enter or exit these areas at numerous points out of bow range. However, using the results of this study to fine-tune your hunting setups can greatly increase your odds of hanging a tag on a mature buck this fall.

According to Kinkel, "One of the best hunting locations is a valley or bottomland food source with habitat edges running from adjacent uplands down descending secondary points and intersecting with the food source. Hunting habitat edges that run from thick cover in valleys/bottomlands up the spine of secondary points to a ridge-top/upland food plot also can be very productive. And, don't overlook those seldom-used, unmaintained roads."

In addition to helping locate the best hunting locations on a property, the results of this study also can be used to better distribute hunting pressure. A common mistake by hunters is over-hunting a handful of areas while avoiding others altogether. Savvy hunters realize that mature bucks are extremely sensitive to hunting pressure and will quickly learn to avoid those locations during daylight hours. Identifying numerous hot spots scattered throughout the property can greatly increase hunting success.

Thankfully, armed with the latest "Whitetail Science," researchers and hunters alike continue to learn more about North America's most-hunted and most-important game animal—the white-tailed deer.