I hadn’t checked a certain trail camera in an entire week. When I did, it had captured images of not just one behemoth buck, but three. With the whitetail season growing short, this was obviously an energizing development. The spot was a sensitive one on the fringes of thronged bedding ground, a textbook staging point where bucks appeared early in the evening and late in the morning. Hanging a treestand would prove risky — at least during the heat of the rut, and because I wanted to climb aboard right away.

I slipped in at midday, erecting a hang-on stand as quickly and quietly as possible, which meant I employed minimal steps and conducted zero cutting. The stand was set on a point overlooking the bend of an ancient logging road. Situating the perch slightly above the higher travel-way required climbing 45 feet off the ground. I used multiple tree branches to reach this altitude. With the deer season well under way, my collection of Hunter Safety System LifeLines was spread thin, I had no time to retrieve one from another site (feeling an urgency to get back into a tree), so the treestand stood without that basic safety ingredient.

After five morning sits — when winds allowed sitting that stand — I’d seen exactly one doe. That fifth morning, following 6 hours in sub-zero temperatures, I figured the gig was up. This is common in north Idaho big woods, an estrous doe sparking a few days of action, but that action evaporating after she is bred. I’d missed the boat.

I was contemplating this, my next move, where those bucks might have gone. According to my watch, it was 10 a.m. I unclipped my HSS harness and started out, mind preoccupied with possible alternatives, forgoing my standard climb-down prep talk. You know, like, “This could kill you, so pay attention to what you’re doing.”

I do remember a branch breaking, likely frozen due to bitter cold. I remember abruptly plummeting, head first, the ground coming up fast. I remember tucking quickly to avoid breaking my neck. I came to at 10:04 a.m., my right arm on fire, convinced I’d just suffered my first broken bone and cursing my idiocy unmercifully.

My arm wasn’t broken. That would’ve been good news, all considered. Instead I’d suffered an inch tear in my right rotator cuff, detached three tendons, and had four substantial muscle tears. This occurred during late November. I underwent shoulder surgery in late February, after enduring a couple months of persistent pain. I started physical therapy 2 weeks later. The 30-foot tumble would result in $17,000-plus out-of-pocket medical expenses.

More traumatic perhaps, for many months I believed I would never shoot a bow again.

Broken Rules

All of this occurred because of the lust for big antlers; short-cutting fundamental safety rules due to addressing a sensitive site while visions of a monster whitetail rack danced in my head. Substituting tree branches for climbing steps is a basic no-no. Natural branches should never be trusted, no matter how sound they appear. Had I taken more time to install even screw-in steps (not the safest option) or better yet, several strap-on ladder sections (which can generally be installed more quickly and quietly), I likely would’ve been spared my fall.

And I will never again climb into any treestand without a LifeLine. Most treestand falls occur while climbing or descending. Unclipping your safety harness during the most dangerous portions of the treestand experience is suicidal — especially when something as simple and reliable as a LifeLine is so readily available. A LifeLine keeps you attached to the tree from the time your feet leave the ground until you touch down again. Even without the LifeLine, things might have turned out differently had I adhered to the “Three-Point Rule.” This means two feet and a hand or two hands and a foot in contact with the tree at all times. I don’t have any vivid recollections of the seconds just prior to my fall, but have to believe I bypassed this regiment.

My wife was also quick to point out another of my follies after I arrived home in great pain. “I didn’t even know where you were,” she scolded!

The Crossbow Conundrum

With spring turkey season quickly approaching and my shoulder still dicey, my surgeon emphatically reminded me I wasn’t fully healed. He prohibited shooting a shotgun. Pulling a bow — given my vastly limited range of motion and loss of muscle function — well, I wondered if that would ever be possible again.

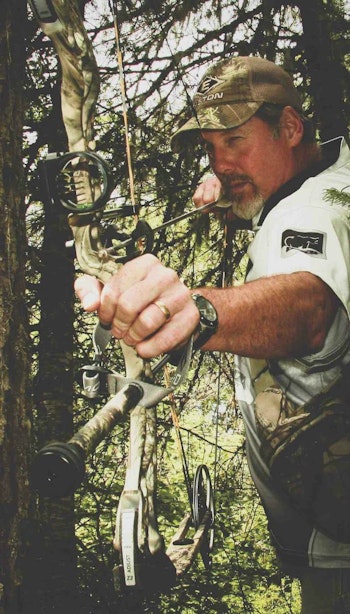

I was initiated into bowhunting in the 1970s and have retained a decidedly traditional bent to this day — I’m not even particularly fond of compound bows. I shoot them mostly because I’m required to keep abreast of the technology to perform my job as an archery-equipment writer, because there are just some hunts when too much is invested or where conditions are such that they make the most sense.

Admitting that, my attitude toward crossbows would be quite predictable. Pre-fall I would’ve rightly been labeled rabidly anti-crossbow. I didn’t have anything against them, in particular, at least in conjunction with private lands in Eastern states where whitetail numbers must often be curtailed to maintain healthy herd dynamics. But in Western settings, where I live and where high-quality tags for elk, mule deer or pronghorn — and I’m talking strictly archery-only hunts — are typically hard won, the idea of piling on a bunch of rifle hunters only taking advantage of better seasons galled me a bit. Like inline, scope-equipped muzzleloaders, the crossbow industry seems to want to have their cake and eat it, too — insisting on invitations to primitive-weapons seasons while also bragging about deadly effect at decidedly non-primitive ranges.

There is no way around the fact crossbows are easier to master than vertical bows (a term I also resent) and can be effectively shot at much longer ranges with much less practice. Eliminating the draw cycle when confronted with intimate game also gives crossbow hunters a distinct advantage. Crossbows have already lead to higher archery-season success rates in many states, and when game managers contemplate increased harvest, it’s impossible to conceive of a scenario where bowhunters are not punished via shorter seasons, lower bag limits or stricter tag quotas.

Yet crossbows saved my 2016 spring. Without any other option, and with a note from my doctor, I received a special crossbow permit from the state of Idaho. By spring’s end I would tag two Idaho gobblers, a Kansas longbeard and an Idaho spot-and-stalk black bear. I thoroughly enjoyed these hunts, made possible by technology I’d once openly ridiculed. But I must also say, hunting with a crossbow in no way compares with real bowhunting. To put it in basic terms, it’s pretty damned easy.

But my attitude toward crossbows had moderated, grateful for the opportunity to enjoy my soul-cleansing spring hunts (after surviving a seemingly endless north Idaho winter). Yet, I still believe in the special regulations I was working under — permits issued to the infirm, elderly or young. I would now be willing to hunt private-land, Eastern whitetails with crossbows. I giddily sent bolts through three Texas hogs well after my shoulder healed enough to shoot a compound bow once more.

Reentry

After my insurance company left me high and dry, and after my surgeon assured me I was sufficiently healed, a bow became an important rehab tool. A Diamond Archery Edge SB-1 with huge draw weight (7 to 70 pounds) and draw length (15 to 30 inches) latitude allowed me to start with kiddy poundage, assuming proper shooting form to stretch my stiff shoulder and work atrophied muscles while doing something I desperately craved. I added a single turn to the limb bolts every couple weeks, until with Idaho’s August 30 archery opener looming, I was shooting 54 pounds of draw weight. I was due for another bump, but left well enough alone, my bow was tuned to perfection and shooting darts.

I’d invested in my standard late-summer scouting, checking cameras weekly so that I had a couple target bucks named, hoping again for velvet success. When one of my target bucks appeared beneath an apple tree 7 days in, his antlers dripping blood and freshly stripped, I wasn’t about to pass him. At 25 yards, quartering-to slightly and growing antsy, I took the shot. I was wielding a heavy-for-spine arrow to aid penetration, but worried about the replaceable-blade NAP Thunderhead Razor — chosen because of field-point flight — wondering if a true cut-on-contact would’ve made more sense considering the poundage involved.

I needn’t have worried, the arrow clipping his facing shoulder blade and sucking into hide. When he turned to flee, my arrow hung from the fletchings on his opposite flank. He barely made it out of sight. In Illinois, a couple months later, I repeated this performance, this time with a 2-inch-wide Rage Hypodermic. And so it went in Texas in December, this time on a whitetail doe and then a buck, plus a couple hefty hogs tipping the scales at around 200 pounds apiece.

Of course I knew my setup was completely adequate, or I wouldn’t have hunted with it at all. I’ve watched my petite wife kill a couple deer and a black bear with 48 pounds and a short 25-inch draw length (I have a 30-inch draw). But after a lifetime of much heavier bows, I admittedly felt handicapped, likely borne of decades-old convictions. Today’s compounds and carbon arrows are much more efficient, and modern broadheads more thoughtfully engineered. Of course, 54 pounds was perfectly adequate, particularly for deer. Though, I did pass a shot at a 330-ish bull elk in September, a shot I wouldn’t have hesitated to take with additional draw weight at my disposal. A willingness to take marginal shots, largely those involving bone, is the only real reason to shoot he-man draw weight. If you spend most of your time hunting deer-sized game — especially from cold treestands — you really don’t need anything more than 60 pounds, simple as that.

Never, Ever Give Up

There were days while enduring slow and painful rehab when I had to learn to conduct many basic tasks left-handed, in those days when I could scarcely lift my right arm above my waist, when I was terrified I would never shoot a bow again. For many months I foresaw a future of crossbow hunting. But I was determined, pushing myself hard during rehabilitation (even when I was forced to go it on my own), ignoring the pain and pushing on. Six months later I shot my first post-op buck.

Nine months after shooting that Idaho buck, I tagged a Florida hog while shooting my accustomed 70 pounds. I was back!

Sidebar: Low-Poundage Terminal Gear

The practice of pairing low-poundage bows with feathery arrows and broadheads is fundamentally flawed. Sure, you’ll enjoy more speed, but penetration suffers. Lethality on big game is about momentum, not speed. Heavy-for-spine arrows and cutting-tip, 100-grain broadheads best serve kinetically-challenged bowhunters.

This would look like choosing low-diameter, thick-walled shafts like Easton’s 4mm FMJ Injexion (9gpi/.460, 9.8/.400 spines), Bloodsport’s Evidence (8.2 gpi/.500, 9.1/.400), Gold Tip’s Kinetic Kaos (7.6 gpi/.500, 9.5/.400), Black Eagle’s Deep Impact (7.6 gpi/.500, 8.6/.400) or Carbon Express’ Maxima RED SD (8.3 gpi/250-.400 spine), as examples.

Combined with conservative, cut-on-contact broadheads such as the G5 Montec, NAP HellRazor, DirtNap Gear D.R.T., Muzzy Phantom SC or Rocky Mountain Advantage, just as examples, penetration is maximized with low draw weights and shorter draw lengths. Standard 100-grain models — instead of 75- to 85-grain models — ensure maximized F.O.C. for straighter flight and a penetration boost.