The tall, velvety, 5x5 New Mexico muley arose from his bed in the sage. He stood straight on, stoic and strong, only 50 yards from where I paused. He was hurt. The problem was, he wasn’t hurt badly enough to be showing any signs of weakness. However, that would play to our advantage. As he challenged me to break my stare, my partner Scott continued to close the distance on his flank.

The hunt began to unfold a few weeks earlier when a co-worker granted me permission to hunt his family owned land. Their property lies just between Cuba, New Mexico, and heaven.

Though I had countless whitetails to my credit, I had never harvested a muley. The thought of pursuing one of these amazing creatures with my bow was exciting. I had no idea what was soon to come.

Arriving at the property, I had barely even closed the gate behind me when a young, tall muley notified me of his presence. His sweeping antlers were hard to miss as he gazed my direction. He was feeding in a low draw among rolling hills of sage. I grabbed my bow and quiver from the back of my Jeep and took a wide berth around the feeding youngster. The large looping semi-circle I calculated required me to remember which dip in the hills he was feeding. Given my pace, it was going to take about an hour to close the distance of only a few hundred yards.

Fast forward those 60 minutes. The good news was I guessed right on which draw he fed; the bad news was I didn’t realize his dad was with him. I watched as his elder alerted and the two pranced away, as if I was more of a bother than a threat.

The following weekend had me up and glassing at first light. My goal was to find where these muleys settled-in and bedded during the midday heat. Getting close would be a second calculation, if needed. Chasing mule deer in the open sage with a bow requires patience, planning and a good bit of luck.

Apparently, I had none of that. No matter how hard I tried, I simply could not close the distance. Either the deer would move while I was slowly easing my way forward, or another set of unseen eyes would spoil my day. I needed help.

Last Call

After a few desperate pleas for help on my Facebook page, I finally landed a friend who was both willing and able to hunt the last weekend of the September mule deer season. The plan hopefully was to double-team on one of the big muleys I had been annoying regularly.

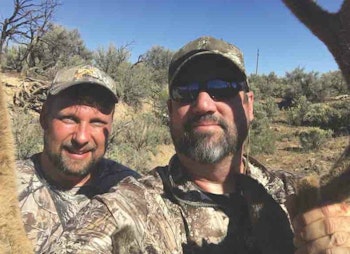

My hunting partner was Scott Carleton, a wildlife biologist with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. His schedule allowed him 2 days, Friday and Saturday, to teach me the ropes of open-sage stalking and to help me tag my first-ever muley. Personally, I didn’t care if it was me or Scott slapping a tag on a muley. My freezer was devoid of venison, and I knew he would be happy to share. Fortunately for me, Scott had been chasing mule deer in the West for quite some time and would provide me the much-needed skills and tactics I obviously lacked.

The weekend hunt did not get off to a good start. My Thursday night call to Scott to plan the morning hunt was met with a flurry of apologies. He forgot to get his tags. He had always purchased his hunting licenses online and forgot that New Mexico switched to a new tagging system. The new tags could not be printed at home and would either have to be mailed or purchased on the spot at the local game and fish office. He swore up and down that he would be waiting at the office before it opened the next morning. This meant I had to glass alone once again and wait until he arrived, hopefully by late morning.

He made the drive to the property in killer time. It was somewhere around 10:30 a.m. that we both sat on top of the knob overlooking the property. It was an eventful morning of glassing for me, and I took my time bringing Scott up to speed.

Opportunity Knocks

I had glassed no less than a half dozen muleys working their way to the rim of a dry creek bed. Most moved off, but I was sure a few lingered in the chest-high vegetation. The little bit of extra moisture the drainage receives during the summer monsoons causes the rabbitbrush and juniper to grow about chest high, the perfect height to give the deer an added layer of security for their daytime beds. When bedded, the knee-high sage surrounding the drainage just doesn’t grow tall enough to hide their velvet antlers.

We continued to glass from the knob. Finally, about midday, a tall, velvet muley stood up and tussled with a nearby juniper. He was soon joined by another. Both were decent-size bucks. We watched as they slowly picked their way toward the rim of the overgrown creek bed. After 30 minutes of lollygagging, the two finally pitched into the steep, inviting cut. Now was our chance to make a move. We quickly devised Plan A and set it in motion.

With the wind in our favor, we closed the distance and pinched off both ends of the drainage, Scott on the west, me on the east. The 20-foot earthen walls not only offered a treestand-like view into the drainage, but it also limited possible escape routes. Our plan was to slowly converge along the rim and either sneak up on an unsuspecting muley or gently push one of them to the other hunter.

Ready, I sent a text message to Scott and informed him I was in position.

His reply, “I shot the big one!”

I stood there for a second debating whether or not he was teasing. His straightforward “Yes” reply to my “Are you serious?” response eliminated all doubts.

I met Scott down in the drainage close to where the buck was standing when he released his arrow. As luck would have it, Scott had peered over the edge and the giant muley was bedded in the shade immediately below him. Sensing something menacing from above, the tall-racked muley jumped to his feet, bounded about 30 yards, stopped and turned to identify the danger.

That’s when the 28-inch carbon arrow made a complete pass through.

Scott was sure of his shot, but after finding his arrow, I wasn’t quite so sure. The lack of blood and the dark bile-like liquid suggested he hit a little further back than he had hoped. Regardless, Scott’s description of the deer’s exhaustive effort to climb the embankment followed by a head-down labored walk, gave us hope the muley was somewhere close by.

We gave the deer 90 minutes before we took up the trail. We didn’t want the buck to sit too long in the midday heat.

Within a few minutes of taking up the trail, we realized he wasn’t close. The scant amount of blood we found was not a steady flow, rather occasional small pools. Its dark, rich chocolatey color, absorbed by the porous sand, still offered promising hope of a liver shot.

Permission Acquired

About 100 yards from the last sign of blood, we found the buck alive. He hung tight as we approached, but the risk from the oncoming hunters was simply too great. He bolted from his bed, and after a few hurried leaps assumed the prancing gait common of western muleys. He quickly closed the distance to the nearby property line and sailed over the barbed wire. Once safely over the fence, though, his gait immediately changed. He slowed to a labored walk, weaved his way about 40 yards through the neighboring sage, then dropped forcefully, as if his legs gave out.

The good news was we knew exactly where he was bedded, but the bad news was we now had to hike back to the Jeep to secure permission from the neighboring landowner — the proverbial clock ticking. We had about 4 hours to recover this deer before the light faded and the scavengers started their rounds.

Within an hour we had received word that the neighbors were good with us chasing the deer on their property, their only request was that we send pictures! Our hope was the buck’s exhausted fall an hour earlier was his last. As we approached the fence line, our hopes were dashed. We saw the tips of his antlers turn in our direction as we eased to within 60 yards. He still had all his faculties.

That’s when we made the decision, we had to get another arrow in him.

We quickly drew up Plan B, where I was to do a large circle downwind and approach from the west. If he replicated his last getaway, he would leap back over the fence and quickly lay down where Scott would be waiting with an arrow nocked. I made my looping approach.

Unfortunately, the mature muley had other thoughts. Instead of sauntering in Scott’s direction, he rose, locked eyes with me and engaged in a stare down. He wasn’t going to budge unless he had to. Scott noticed the lockdown we were in and used it to close the distance.

As Scott eased within 30 yards, I could see him trying to find an opening for a shot; it was only seconds away. And then the buck was gone. He didn’t step. He didn’t turn. He didn’t even acknowledge the threat over his right shoulder. He simply whirled and bounded off to the south, putting a quarter-mile between us.

Change of Plans

With just over 2 hours to go before sunset, it was time for Plan C.

This deer was dying, but he wasn’t dying anytime soon. Our only hope was to push him back onto the property where we began our pursuit, hope he expired in the night, and then find him in the morning.

Our first circle to where we thought he bedded was a bust. No deer and no sign of where he disappeared. I had tried convincing myself that maybe the big muley wasn’t mortally wounded after all. I even suggested it to Scott, but he would have none of it. Scott conducted one more wide circle, sweeping back and forth where he was last seen. Lo and behold, as I was searching for sign, I heard a holler from Scott who was far to the south. There was the buck, prancing in my direction. He bounded no more than 50 yards to my right, making a beeline toward the now distant creek bed where he was first wounded. He made the leap over the barbed wire with little effort.

Back on the hunting property and far away from his pursuers, he slowed to a labored but steady walk. Scott and I watched as his antlers faded into the contours. He was back in the river bed, a place he felt secure.

That’s when we called it. Though we still had no deer, he simply wasn’t ready to die just yet. But, I had memories that were going to last a lifetime. I inhaled deeply before heading off in the direction of the jeep, I wanted to savor the bittersweet scent of sage.

Luckily, after an extensive 3-hour search the following morning, we recovered the beautiful 5x5 muley. Most of our tracking took place in the dense foliage of the river drainage. However, we did not find any blood, only an occasional track and the faintest of signs where an animal had passed. As luck would have it, we weren’t the only one on the deer’s trail. During the night, the coyotes had found the buck, which had been brutally torn apart. Though we were able to salvage only a small portion of the meat, I looked forward to the memories of the hunt shared with a great friend over a meal of venison steaks — seasoned with a subtle hint of sage.

A Wild Taste

Shortly after our mule deer hunt, I prepared the little bit of meat we recovered. As luck would have it, the main offering was a beautiful cut of backstrap that fed the family and a few of our closest friends. The rest of the meat, mostly the front shoulders, was turned into my world-famous deer jerky, delightfully seasoned and dried to perfection. Needless to say, the bounty did not disappoint.

A few days later, I relayed the hunting story to a long-distant student of mine who never had the fortune of eating venison. She asked me to describe the taste. Given the memories this hunt conjured, I had pondered my answer for a bit. I did not want to do a disservice to the animal that frustrated me for so long but in the end, rewarded me so greatly.

My friend was quite surprised when my description of the meal did not consist of fine texture nor extravagant flavor. Rather, I described each bite as a powerful emotion. In fine detail, I elaborated on the nervousness of the unsuccessful stalks amidst the watchful eyes as well as the disappointing appreciation of their seemingly unbeatable senses. After seeing my quarry bound away in a “ha-ha, see-you-later” type gait, my appetite for success grew. The strongest tasting bites described were of the heart pounding stare down in the sage followed by the heart breaking sight of a wounded animal fleeing. Opposing flavors but equally strong and powerful. However, by far, the most satisfying morsel of all was the elation of discovering the animal where it had finally come to rest. The joy and thankfulness of an incredible hunt left the sweetest aftertaste ever imagined.

My non-hunting student was equally overwhelmed with the taste, yet all she chewed on were words. Since that time, she has picked up a bow for the first time and is more excited than ever to consider a new hobby. I believe I did well with my description.

Sidebar: Tracking Game

Regardless of how much we practice at the range, extreme field conditions and adrenaline bursts sometimes result in a misplaced shot. Recovering a poorly struck animal often requires much more skill than simply following a breadcrumb trail of blood. You must not only think like the animal, but you must also visualize and anticipate their change in behavior once they are wounded.

Depending on shot placement, you may want to give the animal plenty of time to expire. We all know this and practice it. Sometimes, however, you may not be afforded the luxury of time. Extenuating circumstances such as high temperatures or excessive predation in the area may require you to try to get another shot into your wounded quarry. Tracking an animal with a less-than-ideal hit may be difficult if the blood trail is weak or nonexistent. Notice I said difficult, not impossible.

The key here is not to give up. Contrary to what many hunters believe, all is not lost when a blood trail dries up. You can still successfully track an animal if circumstances are right and you keep a positive attitude.

This is when you must truly kick in your hunting skills. Knowledge of the animal and its tendencies will reveal the subtlest of clues. Sometimes they’re easy to see like a well-defined track, others not so much. A laid-over sedge or an upturned rock could indicate where a wounded animal paused or possibly stumbled. Being able to track down and recover an animal is often more rewarding than it simply dropping it in its tracks. Without a doubt, it adds another layer of memories to an already exciting hunt.