By JOHN MCCOY | The Charleston Gazette

RIPLEY, W.Va. (AP) — Boiled down to its essence, black powder cartridge silhouette shooting is all about making a bang and listening for a clang.

Shooters fire 19th-century rifles at distant steel targets, some of them so far away it takes a couple of seconds for the bullets to arrive there and another second or so for the sound of a hit to echo back to the shooter.

“It's a really addictive game,'' said Bob Frame of Ripley, one of West Virginia's most enthusiastic practitioners of this rather arcane pastime. “At the distances we shoot, sometimes you can barely see the targets. The amazing thing is how often we hit those targets using pretty much the same rifles and sights people used back in the 1870s and 1880s.''

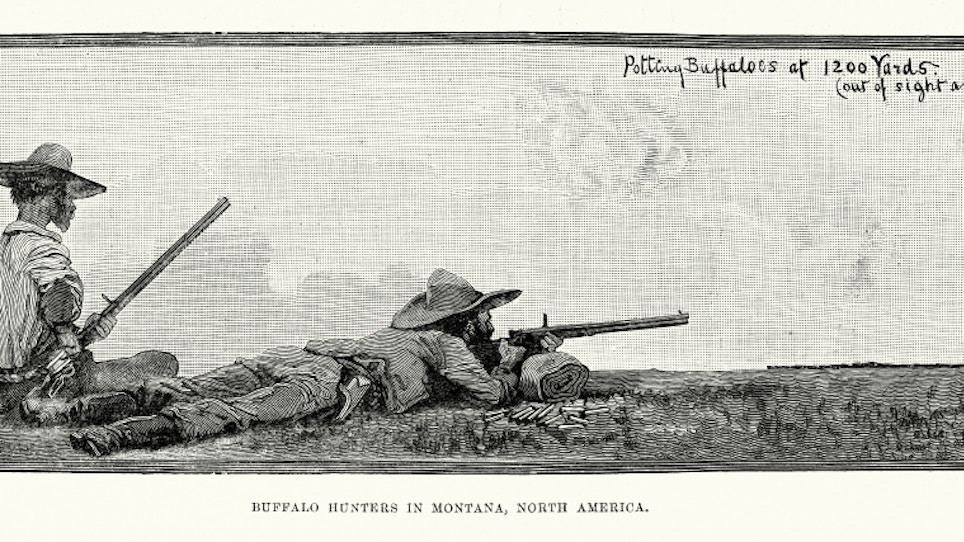

Most black powder silhouette guns are modeled after the legendary Sharps rifles made popular by the Great Plains buffalo hunters of the American West. The rifles, which featured rock-solid actions and highly accurate ladder-style or Vernier sights, could take down buffaloes, elk, mule deer and other big-game animals at ranges greater than 500 yards.

Silhouette targets are thick sheets of steel cut in the shapes of animals hunted during the mid to late 1800s, the prairie chicken, the javelina (a wild pig), the turkey and the ram sheep.

Chickens measure 13 inches wide by 11 inches tall. Pigs are 22 by 14 inches, turkeys 19 by 23 inches, and rams are 32 by 27 inches.

“We shoot the chickens at 200 meters (656 feet), pigs at 300 meters (984 feet), turkeys at 385 meters (1,263 feet) and rams at 500 meters (1,640 feet),'' Frame explained.

“At the distances we shoot them from, the targets all appear to be about the same size. Some are harder to hit than others, though. Everybody thinks the chicken would be easiest to hit because it's closest. Actually, the pig is the easiest to hit.''

Frame said novices often look at the ram, sitting a third of a mile away, and believe it would be impossible to hit.

“Usually by the fourth or fifth shot, they hit it,'' he said. “That's how accurate those old-school sights are.''

Greg Payne of Elkview, another local black powder silhouette enthusiast, said beginners who connect with those distant targets often share a common reaction.

“The first thing they say is, `I can't even see it,''' he said. “But then when they hit it, they get this gleam in their eyes. That's when you know they're hooked.''

At the distances the targets are shot, the human eye can't bring both the target and the rifle's sights into focus. Payne said Frame has a simple solution:

“Bob said to put the fuzzy little blob of a target on top of the front sight and squeeze the trigger. It sounds too simple, but it works.''

Atmospheric phenomena, wind, heat mirage and even humidity can cause shots to miss. For that reason, many shooters record the proper rear-sight settings for those conditions for future reference.

“We make notebooks and charts on settings and ranges,'' Payne said. “Those give us the basic numbers, and we adjust from there.''

Most of the rifles are .40-caliber or larger, and they shoot bullets that look and feel positively gargantuan by modern standards. The heavy bullets are less affected by crosswinds, but their mass causes them to drop more quickly than a lighter bullet would.

That's where the old-school sights come in. When shooters elevate the finely calibrated rear sights, they must raise their guns' barrels in order to make the front sight line up. The raised barrel sends the shots toward the target on a higher trajectory.

“For example, to hit a ram at 1,000 yards, the bullet climbs 52 feet from the line of sight before it starts arcing down toward the target,'' Frame said.

Like many modern firearm sports, black powder silhouette shooting can get expensive. Although foreign-made black powder cartridge guns can be had for about $1,500, a replica Sharps can cost $2,000 to $2,500. If shooters choose to trick out their rifles with custom-made sights or other components, the tab can go even higher.

Factory-made ammunition is available, but Payne said it's prohibitively expensive.

“Most of us cast our own bullets and load our own cartridges,'' he added. “It doesn't take all that much time, and we end up saving a lot of money.''

With all that outlay, one might expect that black powder cartridge silhouette competitions pay lots of prize money. Not so, said Payne.

“I took fourth place in my division at the national shoot in New Mexico, and I think it paid $16, in `NRA bucks,' about enough to buy a hat,'' he recalls. “If you place in a regional shoot, you might make $3. So you can see we're in it strictly for the challenge and fun of it.''

Payne, Frame and other local enthusiasts compete in monthly shoots at a range near Ashland, Kentucky. Frame said it's the only 500-meter range within relatively easy driving distance. Most of the time, he and Payne practice using scaled-down targets at a 200-yard range at Jackson County's Frozen Camp Wildlife Management Area.

“We're always looking for converts,'' Payne said. “If people want to try their hand at this game, all they need to do is get in touch with us. We have guns and ammo they can use.''

“Everybody in this sport will do anything they can to help someone get started,'' Frame added. “We're a close-knit community, and we have a lot of fun.''

___

Information from: The Charleston Gazette, http://www.wvgazette.com