For 10 years, Ken Byers and a group of friends hunted elk on public land in central Idaho using the savage terrain’s intimidating nature to reduce hunting pressure and concentrate elk populations. However, as wolves moved in, disrupting the normal travel and activity of the herds, Byers and his friends switched to southern Wyoming where the wolf menace had not taken a toll.

Through contacts with members of the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, Byers learned that elk populations were returning to normal in the near-vertical terrain of the Salmon River drainage and, along with two friends, planned extensively to again hunt the rugged mountains.

“Our plan was to go back into the steep drainages overlooking the breaks of the Salmon River to see if the elk had made a comeback,” Byers said. “Mike Luper, VP of marketing for Hoyt; Bert Perault, a young cattle rancher from South Dakota; and I planned an aggressive 6-day bivouac hunt. We only come out with elk.”

“Our plan was to go back into the steep drainages overlooking the breaks of the Salmon River to see if the elk had made a comeback,” Byers said. “Mike Luper, VP of marketing for Hoyt; Bert Perault, a young cattle rancher from South Dakota; and I planned an aggressive 6-day bivouac hunt. We only come out with elk.”

The physical, mental and material preparation for a 6-day quest into near-vertical terrain was a huge challenge. And as the adventure approached, forest fires broke out and access to the trail heads was blocked.

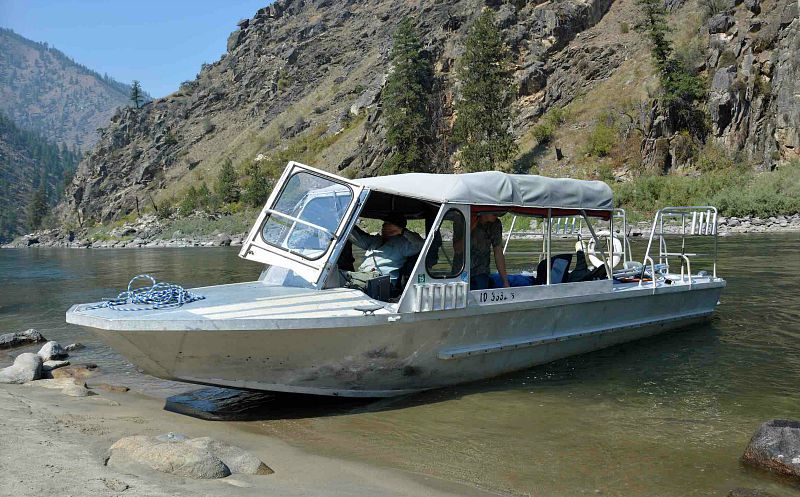

“I considered a helicopter, but it could not legally drop down into the national forest,” Byers said. “Ultimately, we rented a whitewater raft and flew it into a private ranch. Then they jet-boated us up the river to a beach where we stashed the boat.”

Climbing in Cliff Country

“We were so excited as we hit the beach,” Byers said. “Nearly a year of work and planning had finally come together.”

The group used satellite images on their cellphones to navigate and devoted a day to scaling 3,200 feet up the knife edge of the mountain. They began at 1 p.m. in 80-degree heat, clawing and tugging at every piece of vegetation to scale the near-vertical wall.

Halfway up, they ran out of water.

“We had calculated where to get water, but all seeps were dry,” Byers recalled. “We made camp that night after dark 400 feet below the crest, crashed without water and dreamed about it in our dehydrated state. We awoke the next morning with a mile and a half to go.”

Finally, the trio crested the ridge and dropped 2,500 feet down the other side to a rushing stream. “We literally laid by the stream and drank water for the next hour,” Byers said. “We filled up our bottles, cooked a big meal and took a nap.”

Now hydrated, they left the creek and found a bench 400 feet uphill where they made camp for the week. So far, they hadn’t used a call or done any type of hunting. Just before dark a bugle burst across the drainage, a heartening sign that elk were close by.

Now hydrated, they left the creek and found a bench 400 feet uphill where they made camp for the week. So far, they hadn’t used a call or done any type of hunting. Just before dark a bugle burst across the drainage, a heartening sign that elk were close by.

Secret Strategy

Byers had gotten a tip from another avid elk hunter to start bugling at 2:30 in the morning. The idea was to get a bull going in the dark and keep tabs on him. Plus, even pressured elk seem to respond in the dark.

At daylight, the trio headed for the opposite ridge, where a herd bull answered their calls. Dodging several satellite bulls, they spread out and closed on the herd bull.

“I let out my first cow call and immediately heard a bugle, brush breaking and rocks rolling,” Byers said. “Three or four bulls bugled simultaneously, and within minutes I could see antlers coming through the trees. As the bull stepped into a small opening, I put the pin right behind the shoulder, exactly where the arrow hit. It whirled and ran, but I cow-called and kept it within 50 yards.”

Elated with their first-attempt success, the crew swapped jubilant tales as they cut up the bull and packed it down to the stream bed, where the air would be much cooler.

Ken Byers stands high above a rugged Idaho canyon, bugle ready and eyes peeled. Byers used his bugle often throughout the hunt, especially at night, to locate bulls and move into position on them come first light.

Back in camp, Byers believed that the night-bugling strategy had made a difference and once again talked to bulls well into the night. Just after daylight, they found another herd, but swirling winds ruined the stalk. They made a big side-hill swing to avoid scent detection, took a nap, ate lunch and waited for the afternoon thermals to change. As evening approached, bulls began bugling.

Byers now became the main caller and put his buddies above and ahead of his position while he cow-called and raked trees. Bulls bugled in response but would not come out of the dark timber. Perault saw a large herd bull and made a direct stalk. Byers kept calling until he heard a cow bark, a signal the hunt was over. Byers barked back, trying to mitigate the damage even as he mentally resolved to try again the next day.

Suddenly, he heard the sound of a bull gasping for air and realized that someone had scored. The 300-class bull crashed just as daylight faded.

Three for Three?

After a mini-celebration for a prairie rancher who had just killed his first elk, the trio began to field-dress the bull and made a decision. Rather than spend the rest of the night cutting and packing elk in the dark, Perault agreed to return to the carcass in the morning and expend the rest of the day moving the bull down to the cool temperatures of the stream. This gave Luper an opportunity to fill his tag.

Bert Perault made good on his first Idaho opportunity. A perfectly placed arrow put this 300-class bull down in minutes.

Byers continued bugling through the night for a third time and left camp in the morning wondering if it was possible for three unguided hunters to take three elk in 3 days. In addition, the formidable task of packing meat off the mountain had become a reality.

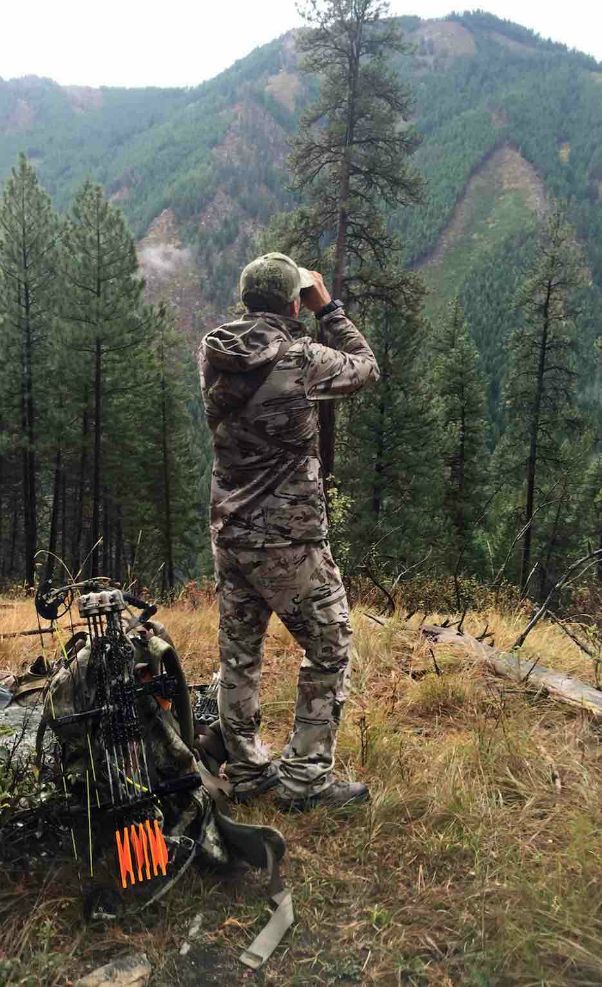

Hoyt’s Mike Luper scans an adjacent mountainside for any sign of the mighty wapiti. The steepness of Idaho’s backcountry can be described in a single word: daunting.

Luper set his sights on a monster-or-nothing strategy, and the hunter’s character was tested late in the afternoon when a small bull approached a cow call and stood broadside at 30 yards. The day ended with an exploratory trek along a pack-out stream. In theory, the route looked promising, yet upon inspection they found a mass of jumbled treetops and debris, an impossible task with heavy packs.

Arriving back in camp in the dark, the two men expected to find their buddy waiting with a warm welcome. However, they found no sign of Perault. Cutting and packing the elk downhill took effort, yet it should have been attainable in a full day. After an hour had passed and Perault had not appeared, Luper hiked up the mountain to the kill site, but there was no sign of Perault. Byers bugled, cow-called, whistled and eventually shouted to his friend — without a response.

Tragedy had touched the Perault family in the past year. A grandparent suffering with Alzheimer’s wandered away from the home and froze to death, while just 6 months earlier Perault’s mother passed away very unexpectedly. The series of family tragedies added an aura of intense concern. Had the 24-year-old accidently cut himself with a knife? Gotten lost? Become seriously ill?

Luper and Byers feared the worse and believed they’d have to begin the next day with a somber search for their friend. Unable to sleep despite their exhaustion, the two were elated when a light appeared below camp and slowly progressed up the steep hill. The rush of the fast-moving stream had drowned out their calls, and Perault had spent the entire day packing and preparing the elk.

One Tough Tomorrow

Elated with their partner’s safe return, the three men grappled with the enormity of the task that lay ahead. The trio chose to end the hunt and pack out to the river. With so much elk meat to carry, they rolled hunting outfits and non-critical gear in a tarp and stashed it under a log. After cleaning up camp, they went down to the creek, loaded the elk meat and headed back up. The original stream-bed path abandoned, the trio hoisted their 150-pound packs and struggled upward. Perault was heartbroken to leave his elk cape behind, but the extra weight was simply too much to haul.

Elated with their partner’s safe return, the three men grappled with the enormity of the task that lay ahead. The trio chose to end the hunt and pack out to the river. With so much elk meat to carry, they rolled hunting outfits and non-critical gear in a tarp and stashed it under a log. After cleaning up camp, they went down to the creek, loaded the elk meat and headed back up. The original stream-bed path abandoned, the trio hoisted their 150-pound packs and struggled upward. Perault was heartbroken to leave his elk cape behind, but the extra weight was simply too much to haul.

Going cross-country, the first 3 hours were a nightmare in a windy, rainy snowstorm that made the steep grade more slippery. Byers and Perault had to throw their antlers ahead, make two steps and repeat the process. The constant friction from brush and climbing over deadfalls added greatly to the struggle.

As darkness fell, they reached the top of the mountain totally exhausted. “We started a big campfire,” Byers said. “We had gone the whole hunt without a fire until the pack-out when we cooked elk on an aluminum arrow. The fire helped to dry our boots, socks and gear. Just before dark we saw a 350-class bull, the 20th of the trip.”

As darkness fell, they reached the top of the mountain totally exhausted. “We started a big campfire,” Byers said. “We had gone the whole hunt without a fire until the pack-out when we cooked elk on an aluminum arrow. The fire helped to dry our boots, socks and gear. Just before dark we saw a 350-class bull, the 20th of the trip.”

Rising early, they ate their last batch of oatmeal as a thick fog rolled in — so thick that visibility was only 50 yards. Navigating blindly, the trio walked for an hour until the fog finally lifted and revealed a devastating circumstance. They had dropped down the wrong side of the knife edge, which meant they had to backtrack a full hour uphill (again).

Deadfall Descent

“Two hours into the trek we finally began taking steps down the mountain,” Byers recalled. “Temperatures rose to 75 degrees, and it got so steep that we had to hand packs to each other, dodged two rattlesnakes and constantly struggled. Every step was treacherous. If you stepped on a rock or rolled an ankle, you’d be gone.”

The trio had to drop down 3,300 feet to get to the Salmon River with no trails to follow. Two-thirds of the way down, the terrain became too steep to walk, and the hunters resorted to sitting on their bottoms, making short slides and digging in their heels to stop. They slid over waist- to head-tall trees, which helped control the speed and direction. “It was wild,” Byers said.

Luper took a variant path around a rock and was cliffed-out. The terrain was too steep to climb up or down. With his life literally on the line, he was forced to slip off the pack of meat and his bow and watch it crash down the cliff, exploding upon impact. It wasn’t an easy choice, but it was one that saved his life. Unburdened by the weight, he maneuvered to get out of the jam and down to his pack.

“We had been out of water for 3 hours and were completely exhausted as we reached the beach of the Salmon River,” Byers said gravely.

As they loaded the raft, Byers saw Luper coming down the mountain and knew something was wrong. His face was distorted and his gear in shambles. Reaching the bottom, he collapsed in total exhaustion.

The three men regained their strength and began assembling and hand-pumping the raft for the 10-mile drift to the take-out point. Battling swift currents, rapids and impending darkness, they arrived with 5 minutes of daylight left.

At 11 p.m. the trio enjoyed the best-tasting pizza of their lives, although their bodies were so punished they could eat only half the meal. This unimaginable hunt on public land required 120 percent of each man’s ability and, from an adventure perspective, was 1,000 percent successful.