The South Dakota sun was directly above me as I started to grow drowsy. I had been sitting in a ground blind, staked in a sparse alfalfa field since before dawn. Hoping to waylay a pronghorn, I was becoming uncomfortable due to the heat. With no pronghorns in sight, I started glassing the endless prairie. I was startled to my core when my binocular revealed a small herd of bison, far in the distance. While the herd was privately owned, watching it move across the landscape stirred something deep within my soul. I decided I would someday hunt the massive beasts with my bow.

A decade later, on the cusp of my 40th birthday, it was time to make the dream a reality. I threw myself into research, spending hours searching online for information on hunting bison. The facts are, true free-ranging bison either require a supremely lucky draw for one of the limited tags available in Alaska, Arizona, Montana, Utah and Wyoming, or by booking a hunt in British Columbia’s Pink Mountains. I didn’t want to wait my entire life for a lucky draw, or raid the kid’s college fund for a Canadian hunt, so I had to discover something else.

There are numerous ranch hunts for bison across the country, differing greatly in adversity of hunting. Some can undoubtedly be called “shoots” rather than hunts, where the bison are kept in small paddocks and acclimated to humans. I had no interest in a shoot for such a majestic animal.

Lower Brule Bison

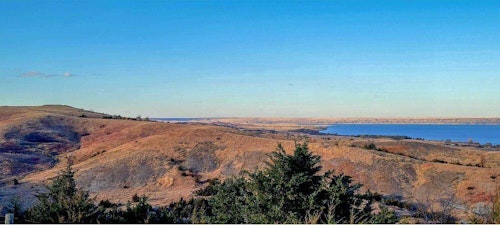

On a cold winter day, I stumbled across the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe Department of Wildlife, Fish and Recreation website. The Lower Brule Reservation, belonging to the Lower Brule Sioux, or Kul Wicasa Oyate, is located on the western banks of the Missouri River and Lake Sharpe in south-central South Dakota. The reservation stretches more than 200 square miles of rolling mid-grass prairie, irrigated and dryland farmland and rugged river breaks.

Reading further, I learned that the tribe offers a variety of hunting, fishing and trapping opportunities to non-members. Of special interest to me, the tribe maintains an elk herd in one land unit and a bison herd in three land units. I wasted little time in calling for more information.

I reached Ben Janis, the director of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe Wildlife, Fish and Recreation Department. He explained that bison were brought to the tribe’s land during the mid-1970s as a way for people to reconnect with the culturally and spiritually important animal. Additional animals were added during the 1980s and 1990s. In cooperation with the National Park Service and Wind Cave National Park, excess bison were transported and released on the Lower Brule Reservation.

Wind Cave bison are unique in that, along with those from Yellowstone National Park, there are no cattle genes in their DNA. The majority of bison across the country, in both wild and private herds, have some cattle genetic intrusion.

Ben explained that the three bison units have exterior fences to reduce the chance of the animals wandering off the reservation. In an ideal world, the animals would roam completely free, but, even in South Dakota, this doesn’t fit with modern land use. It’s an unfortunate reality.

I asked Ben if the animals are rounded up each year for inoculations and health tests, which is a common practice in parks and private herds. I was happy to hear that the Lower Brule herd was not ear tagged, rounded up or given any shots. He stated simply, “They are wild animals.”

Biodiversity is very important to the tribe. Not only do they manage the land for game species, but they also have reintroduced the black-footed ferret to the land. One of America’s most endangered species, the mink-sized member of the weasel family preys on prairie dogs, among other small mammals. The tribe has successfully documented reproducing pairs on the reservation, restoring yet another historical animal to their ancestral land.

A number of Indian reservations in the Central Plains and West manage their bison numbers through hunting. The fees paid for tags, Ben explained, help the wildlife department pay staff salaries and management costs. After thanking him for his time, I had barely hung up the phone before logging on and applying for a bison tag.

There are four tag types offered: cow, young bull, management bull and trophy bull. A prospective hunter can purchase up to five applications at $10 each. Numbers of tags for each type vary each year, according to management needs. I purchased applications for a cow and management bull. (Note: In 2022, cost of a Lower Brule cow bison license was $1,875; young bull, $2,500; management bull, $3,250; trophy bull, $4,000. Number of bison tags allocated to non-tribal members in 2022 were cow, 15; young bull, 5; management bull, 3; trophy bull, 1.)

I was sitting in a co-worker’s cube, no doubt discussing the upcoming field work season, when I checked the email on my phone. The first email read: “Congratulations, you’ve drawn a cow buffalo tag!” It was celebration time!

Learning About Bison

That summer, my significant other Melanie and I took our four kids to the Black Hills of South Dakota for a family vacation. We had perfect weather, enjoying the attractions the area offers. Of special interest to me were the bison herds in Custer State Park and Wind Cave National Park. Both parks are visited extensively by tourists, and the bison show little fear. Despite the decidedly non-wild feeling of the parks, it was exhilarating to be close to the bison, even if it was from the front seat of a car.

As my tag was for a cow, I spent plenty of time watching the animals, deciphering the differences. Because both sexes have horns, it was critical to understand how to tell them apart. The old, mature bulls were easy, as they towered above the herd and sported wrist-thick, curling horns. The bigger issue was the younger bulls and mature cows. The young bulls didn’t sport the mass of the mature animals, and at a glance looked like large cows. As I watched, I began to learn how to identify a large cow. The cow’s horns curl back sharply. A bull also had a tuft of hair from male parts, which a cow lacked. Lastly, the head of a cow was a bit narrower, lacking the large forehead of a bull.

Finally, it was October. I was admiring the taxidermy at the Lower Brule Wildlife’s headquarters when my guide and Herd Technician Earl Laroche entered through the creaky door. He instructed me to toss my gear in his truck outside while he filled out some paperwork. I grabbed my backpack and bow and waited.

Things took a bit of a turn south when he jumped in the cab. “Did you bring a rifle for backup?” he asked. “It can be difficult to sneak close to these bison.”

I informed him I had not, but that I was confident in my bow and could place my shots out to 50 yards with accuracy. The previous evening, after checking into my hotel room at the local casino, I found some round bales and shot my bow, ensuring everything was perfect after the drive.

With a sigh, he put his truck into gear, and we entered the Missouri Breaks in search of a bison.

A half hour later we glassed up a large herd of mixed animals. There were no large bulls, but at least 30 younger bulls, cows and yearlings grazed peacefully in a bowl, surrounded by higher prairie and patches of Rocky Mountain juniper trees. The cool morning was evident, as steam rose from each animal as they exhaled in the still air.

“With that many eyes,” Earl said, “it won’t work for the two of us to stalk.” He pointed out a few obvious cows and suggested a stalking route that would take me within range of the herd.

My heart was hammering in my ears as I hiked the ridge, out of the bison’s sight. Unusual for the Great Plains, on this morning there was very little wind. I pushed through the trees as I worked my way around. I finally eased within range of the hill, noting a bull grazing in the dry grass. Contemplating my next move, a puff of wind hit the back of my neck. The sound of thundering hooves suddenly arose from the other side of the hill as dust floated skyward. Rushing up to get a better vantage point, I witnessed the herd, flowing like water, rush across the land and out of sight.

An hour later the same thing happened. I tried to ease into bow range, but the herd either heard or smelled me and then thundered away, this time deep into the rugged breaks. With my head hanging low, I hiked back to Earl’s pickup. It didn’t pay to keep chasing this herd, he said, as they were spooked and would take hours, if not days, to settle down. The best bet was to try another area, with a herd that had seen less hunting pressure.

Moment of Truth

Forty-five minutes later, after a pleasant conversation while driving through gorgeous country, we entered another area with bison. Instead of rugged breaks, this unit was characterized by low grass and rolling hills that stretched to the horizon.

Earl’s pickup chugged across the prairie, and we soon spotted a bison herd, shimmering in the distance. Stalking was going to be extremely difficult, but Earl had a trick up his sleeve. “We will drive toward them until we are within a few hundred yards,” he said. “I’ll drop you off in some taller grass and then drive away. Hopefully they will watch me, giving you a chance to sneak within range.”

Soon I was on my knees in the prairie dirt, watching Earl’s truck driving at an oblique angle across the grass. The herd continued feeding, with a few animals on the edge watching the truck. I scurried closer, staying low to the ground. Finally, when I felt close enough, I hit the nearest animal with my rangefinder — 45 yards.

I wasn’t hidden well, and the animals soon noticed me. While they weren’t taking flight, they knew something was amiss. Things began happening quickly, and I frantically searched for a cow. I was able to focus on a large cow toward the edge of the herd. As they jostled for position, she took a few steps into the open. My bow was up in a flash.

Settling the bowsight pin on her chest, my arrow arched through the sky and struck home, albeit toward the back of her ribcage. She jumped forward before trotting into the center of the herd. The others smelled blood in the air and dust swirled as I tried to melt into the ground.

It was easy to maintain contact with my cow, as the arrow hadn’t passed through. Unfortunately, a bull rushed past her and broke the arrow. She walked toward the edge of the milling herd again, wanting to move away from the bull.

My second arrow was gone as soon as she presented another shot, driving deep into her chest nearly up to the fletching. The results were immediate. She trotted back into the herd, and I lost her in the dust. The majority of the herd broke free and pounded across the prairie. A few animals remained, using their horns to prod the cow back to her feet. Once they realized she was down, they left. Within seconds the prairie was silent, and I heard only the roaring of blood in my ears.

Giving Thanks

I had a few moments alone with the magnificent bison as Earl headed my way. I always feel a twinge of remorse after killing an animal, but it almost seemed like too much to have taken such an incredible life. I said a brief thank you to the animal for her life and the experience on the prairie.

An hour later, after loading up the cow with help of a UTV, some rope and sweat, we rolled back into the headquarters. We attached the carcass to a steel gambrel and lifted the great animal up with a utility tractor. With sharp knives and the entire afternoon in front of me, I began working.

Five hours later, all that was left were bones. A large cooler was filled with trim meat, the four quarters were in game bags, the hide folded, and the skull cleaned. The amount of lean, red meat was mind-boggling.

My hunt for a bison was not a wilderness backpacking hunt, nor was it a treestand endurance fest. It was totally unique, something well worth the experience. Across the West and Great Plains, numerous Indian reservations offer bison hunts. Hunting this special animal, so important to the culture of Native Americans, is truly an experience of a lifetime.

Sidebar: Bow Gear for Bison

My cow bison was estimated to weigh approximately 1,000 pounds. An animal of that size requires stout archery equipment. I shot my old standby Mathews compound, set at 70-pounds. My arrows were Carbon Express PileDriver DS Hunter 350 shafts. While I typically use 100-grain NAP Shockwave mechanical broadheads for deer, I chose 125-grain Magnus Stinger four-blade fixed broadheads for bison. Like other big game animals, a bison’s shoulder covers some of the lung area, so accurate shots are a must. The animals are tenacious and tough, too.

Sidebar: Bison Hunting on Indian Reservations

Along with the Lower Brule, there are several other Indian reservations that offer bison hunting. As rules and regulations are subject to change, the best way to obtain more information is to contact the tribes directly.

- Lower Brule (South Dakota): www.lowerbrulewildlife.com

- Standing Rock (North and South Dakota): www.gameandfish.standingrock.org

- Rosebud Sioux Tribe (South Dakota): www.rstgfp.net

- Oglala Sioux, Pine Ridge (South Dakota): www.oglalasiouxparksandrec.net

- Crow Nation (Montana): www.crownationbuffalohunt.weebly.com

- Fort Peck Reservation (Montana): www.fishandgame.fortpecktribes.org/buffalo