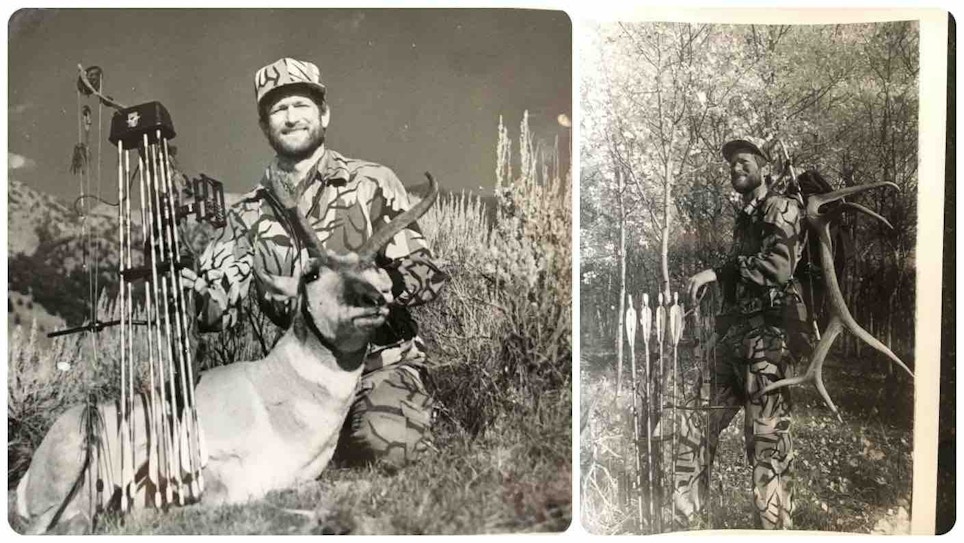

The oldest print images the author could find showcasing his own bowhunts were from the early 1980s. Both of these animals were killed on public land in Montana.

Heraclitus, a Greek philosopher of the late 6th century BC, once sagely observed, “Change is the only constant in life.” That sentiment certainly applies to hunting the western states today. It’s so different from when I started in the late 1960s/early 1970s I can hardly recognize it.

Some big differences? In 1970 the U.S. population was estimated at about 200 million; in 2023, 338 million. From 1961 until the early 1990s, there were only three television networks (no cable), and it wasn’t until October 29, 1969, that ARPAnet — the precursor to the modern internet — delivered its first message; the internet wasn’t in full swing for another decade. Travel by air was a luxury, and gas averaged about 36 cents/gallon. Everything was less expensive. Statistics show that a 1970 U.S. dollar would purchase the equivalent of $7.71 in 2023 dollars.

Pay to Play

I grew up in southern California, went to college in Sacramento, and annually started hunting out-of-state in the mid-1970s. The cost of a nonresident hunting license and a deer or elk tag was very reasonable, and myself and two buddies hunted at least two different states every fall on our meager incomes. There were no draw tags and no hunter safety card requirements; you just showed up, bought tags and licenses over-the-counter, and got after it. There were no “landowner tags,” and getting permission to hunt private land was difficult, but not impossible, for the unattached nonresident.

There were no smartphone hunting apps, only topographic, national forest, and BLM paper maps, and a compass. You discovered property boundaries and hidden access points to public land by painstakingly long research sessions in the local library and state and federal lands offices. I had a file cabinet filled with my notes as well as state hunting regulation booklets and maps for planning.

Increased Pressure

Also, hunting pressure in general, and bowhunting pressure in particular, was much lower than it is today, especially if you were willing to get away from vehicle access (there also were no ATVs back then.) I started backpacking in California’s Sierra Nevada mountains when I was 16, and learned in my early 20s that if I backpacked even a mile away from easy access, hunting pressure dropped a hundred-fold. Now everybody backpacks, it seems. Bugling up a bull elk with the primitive calls we had back then — no, there were no diaphragm-type calls — was relatively easy. With little pressure, they had no reason to be “call shy.” Of course, with the archery tackle we had back then (and no laser rangefinders), you had to get right in an animal’s face to be able to make the shot. And elk and mule deer populations were strong, at least until the reintroduction of apex predators such as wolves and grizzlies, which have had a serious impact on ungulate numbers. You could freely hound hunt, too, so black bear and cougar populations were kept in check.

As Heraclitus noted, everything has changed. Today, hound hunting is banned in many states, apex predators are eating huge numbers of game animals, and the number of hunters who want to hunt out West has skyrocketed, forcing states to limit hunting pressure by doling out tags via a complex draw system built around, in most states, the issuance of either preference or bonus points. The odds of drawing coveted tags is extremely low, even for residents. For example, I lived 15 years in Arizona, and drew only two archery bull elk tags during that time. If you’re well-heeled, you can bypass the draw system by purchasing a governor’s tag for many tens of thousands of dollars, or a landowner tag costing many thousands.

Sadly, getting permission to pursue western big game on private land is essentially a thing of the past. That forces those who don’t draw a tag to target states with OTC tags such as Idaho, New Mexico, Colorado, and Montana — and fight the crowds. I’ve bowhunted elk in such a unit in Montana the past two seasons (killed a nice bull the first year on day 6; hunted 18 days last year with no shots), and believe me when I say the bulls have PhDs in hunter avoidance.

Drawing a Tag

Many serious western hunters turn to a tag application service such as WTA TAGS (Worldwide Trophy Adventures) like I do, which helps navigate the complicated process and helps build points in multiple states over time, a critical component of modern-day western hunting. If and when you do draw a coveted tag, odds are you won’t know the lay of the land, hampering your chances unless you shell out for a pricey guided hunt. Know, too, that as a nonresident your competition often comes from locals whose lives are structured around hunting their hometown areas. While internet research and smartphone apps can help you get started, like hunting everywhere, there is no substitute for hands-on experience on a piece of ground. You have to pay your dues.

I guess the biggest difference today is that, with few exceptions, is it difficult, if not almost impossible, to travel out West at the last minute without the deep pockets required to buy landowner tags. You have to plan ahead, apply for big game tags many months in advance, and be willing to hunt whatever state/unit in which you can draw while hoping someday you will draw a coveted tag. Regardless, you have to work very hard at it to be successful.

In that, I guess some things never change.