Savage’s 14 Classic in .243 is mostly ordinary. The author’s rifle is very accurate and has earned “favorite” status. (Photo: Wayne van Zwoll)

In your rifle rack, I’d no doubt find hardware lacking in mine. But you don’t have Dick Nelson’s .22-250. He sold it to me some years ago, after his last rifle match. We’d fired in many small-bore events, he a great, round-bellied presence continually insisting that in the next relay his bullets would funnel into the X-ring “like trained pigs.” Dick worked on NASA projects — one was the first moon vehicle. Having underwritten college milking Holsteins, I knew nothing of rocket science. Dick didn’t expound on it. He was a modest man who delighted in the company of people who delighted in the simple achievement of a well-placed .22 bullet.

Even if his Remington were not accurate (it is) or had not been well cared for (it was), I’d cherish it. But Dick Nelson and our days perforating bull’s-eyes remain only part of its allure. This 700 of the early 1960s reflects a tipping point rifle design. Iron-sighted, walnut-stocked models would soon be supplanted by variants with “clean” barrels, polymer stocks, Picatinny rails and attorney-approved triggers. Bored for cartridges not yet born when Dick worked at Boeing, they cost more, function well, shoot accurately and lack character. To those of us who once drove to rifle matches on 28-cent gasoline, character still matters.

Dick Nelson owned this 1960s-era Remington 700 BDL in .22-250. It’s one of Wayne’s favorites. (Photo: Wayne van Zwoll)

While pleased by the performance of some 21st-century rifles that have followed me home, I’m hopelessly stuck on earlier rifles as favorites.

What reminds us of good times in our lives survives well in memory and edges out contemporary alternatives. I prefer the quick, compelling beat of early rock-and-roll music to what followed. The early ’60s delivered more optimistic and surely,/ less profane lyrics. Those old tunes bring to mind Saturdays with a .22 under beeches, roosters rocketing from fencerows, my first deer, the comely lass in 9th grade English.

Just so you know, my picks aren’t arbitrary.

I’ve not owned all my favorite rifles — been relegated to lusting after some. As a youth I pined for a Remington 700 BDL in .222. In 1964 it retailed for $129.95. At just 6½ pounds with a 22-inch barrel, it was slightly lighter and shorter than Dick’s rifle, which appeared after Remington pulled the .22-250 from the wildcat shadows by giving it commercial status in 1965. I liked the 700’s lineage.

Ace gunmaker Patrick Holehan built this .25-06 on an M70 action. A superb predator-big game rifle! (Photo: Wayne van Zwoll)

Following World War II, Remington adopted a low-cost bolt-action designed by Merle “Mike” Walker and Homer Young. Walker, a Benchrest shooter, included features to enhance accuracy. The 721 and short-action 722 appeared early in 1948, their receivers cut from cylindrical tubing. The bolt had a clip-ring extractor and plunger ejector. The twin-lug bolt head was brazed in place, as was the bolt handle. Its recessed face enabled Remington to claim the case was supported by “three rings of steel.” The self-contained trigger group, stamped-steel bottom metal and a separate “washer” recoil lug pared costs. Initially a 722 in .222 cost $74.95. Upgraded A and B versions of both rifles were replaced in 1955 with ADL and BDL designations.

I owned a 6mm 722, scoped it with a 4X Lyman Challenger and hunted with it. The 1-in-12 rifling twist was widely pronounced too slow for 90- and 100-grain game bullets (giving .243 rifles with their 1-in-10 spin an edge at market); still, my rifle shot minute-of-angle with both weights. Heavy with its steel bottom metal and 24-inch barrel, that 722 had an honest look and feel. It held predictably to my 200-yard zero and accounted for a Wyoming pronghorn at 420 yards.

In evening dress the 721/722 became the 725, made briefly 1958 to 1961. I had a .243, of which only 998 were built. A friend pried this mint-condition rifle from me for a song. Such charity defies logic.

Remington dropped the 721/722 in 1961 and the following year announced its sequel. The Model 700 offered refinements: trim tang, swept bolt with checkered knob, alloy bottom metal. The stock had a higher, scope-friendly comb. Mike Walker gave the 700 faster lock time and shortened the leade. In .222 Magnum as well as .222, .243 and 6mm, the short-action 700 was a predator-hunter’s dream. Later .223, .22-250 and .25-06 chamberings earned it more plaudits.

Its arch-rival, of course, was Winchester’s Model 70, introduced in 1937 in .22 Hornet and .220 Swift, .250-3000 and .257 Roberts (plus several big-game rounds). It wooed shooters with its lovely lines, Mauser-style extractor, hand checkering. A Featherweight arrived in 1952; the .243 joined the cartridge list in ’55. Changes in 1964 — including springs, extractor and stock — gave competitors a clear passing lane. They took it. Winchester has since restored some early features to the Model 70, and swapped outdated chamberings for those popular now. Sadly, you cannot buy a Model 70 for the last pre-’64 price of $139.

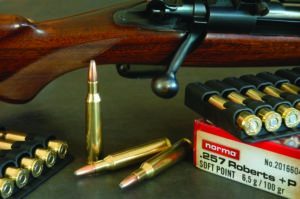

The .257 Roberts was a charter chambering in Winchester’s Model 70. It’s still a fine predator round. (Photo: Wayne van Zwoll)

Among the many rifles I’ve sold in brief moments of insanity was a 1950s-era M70 rechambered from .257 Roberts to .25-06. Otherwise new, it had beautiful wood and, under a 6X Lyman All-American, set my heart a-flutter. A finer coyote-pronghorn-mule deer rifle was hard to imagine. I must confess, on the advice of my therapist, that I’ve also parted with a Super Grade Swift and a Featherweight .243. I’m holding tight to a .25-06 ace gunmaker Patrick Holehan built for me on an early Model 70 action.

I’ve not owned a Mannlicher-Schoenauer 1952 GK. Even when Remington’s 700 was fresh and Winchester accountants were raping the Model 70, the M-S cost a gasp-inducing $198. In .243 or 6.5x55, the Carbine version with a receiver sight seemed to me an ideal “walking” predator rifle. The later 1961 model was better adapted to scopes. M-S actions then were butter-smooth. With the bolt open and barrel up, you could snap the muzzle down and watch the bolt flick forward, strip a cartridge and rotate closed!

CZ rifles of that day weren’t quite that slick, but shared a European heritage (M-S in Austria, CZ in Czechoslovakia). After a production hiatus 1948 to 1964, Ceska Zbrojovka started courting the hunting market. The petite 527 and standard 550 bolt rifles arrived stateside beginning in 1995. Engineered for the small cartridges, .22 Hornet to .223, the walnut-stocked 527 is a delight. Mine, in .221 Fireball, scales less than 6½ pounds, though its barrel is stiff enough for fine accuracy and the slightly muzzle-heavy balance I prefer. Variations abound. A long list of chamberings includes the .17 Hornet, .204 Ruger — and now the 6.5 Grendel. Designed for the AR-15 and loaded by Hornady, the Grendel starts a 123-grain softpoint at just under 2,600 fps. CZ’s 527 fetches from memory Sako’s lithe 1950s-era Vixen, engineered for .222-class cartridges and mid-range shooting at foxes and coyotes.

A watershed year for CZ, 1964 also brought to the U.S. a new Anschutz rifle. Already renowned for its super-accurate rimfires, Anschutz unveiled the Model 54 Sporter in .222. Its rakish stock with skip-line checkering and rosewood caps had a glossy finish to match the metal’s bright, flawless blue. The 54 cost $159.95. I was then no closer to buying a Maserati — though not long thereafter I dug deep for a 1413 Anschutz match rifle. If I could now find a pampered 54 in .222, I’d snatch it up in a wink!

Dating to 1950, the mild, accurate .222 has set Benchrest records and collected many predator pelts. (Photo: Wayne van Zwoll)

Ruger’s stunning No. 1 single-shot rifle arrived in 1966, a sure hit with anyone who admired fine wood, the elegance of Farquharsons and Bill Ruger’s genius. No need to ask if my .243 No. 1B is for sale.

My Savage 14 Classic in .243 won’t match the No. 1’s eye appeal; but it’s supremely accurate and seems to hit whatever it’s aimed at. That Savage’s field record on game has earned it a permanent rack slot.

“Only accurate rifles are interesting,” observed the sage Townsend Whelen decades ago. But that doesn’t mean all accurate rifles are interesting. Rail guns with test barrels the diameter of rolling pins nip one-hole groups in ballistics labs charged with developing loads. Predictable hits from ponderous tooling. No character. There’s a reason Benchrest rifles, ill suited to firing from field positions, still look like rifles and wear beautifully contoured and finished stocks. Appearance matters.

Prefer a tactical look with black components? Many do. Milking gnat’s-lash accuracy is easier if you needn’t massage walnut hugging steel like skin on a peach. Those of us with traditional tastes will endure the expense and idiosyncrasies of wood, and the inconsistencies of slender barrels. We’ll insist on iron sights, because rifles appear naked without them. As a bipod is an unnatural appendage, we’ll install instead a leather sling. Given our rifle’s clean, carnivorous profile, we’ll forego 2-pound, 34mm scopes and attach a slim variable or fixed-power optic in low rings. We’ll leave the rangefinder home. And the smart phone with its ballistic data. We’ll coax that coyote inside 200 steps, or belly to within point-blank range of Br’er Fox.

And if we can’t? Some days, just being afield with a favorite rifle is enough.