Mule deer migrate across half-frozen Fremont Lake in Pinedale, Wyoming. Photograph credit: Mark Thonhoff, Bureau of Land Management

She headed onward toward Jackson Hole, leaving the others behind at Hoback Basin. And you should know that this kind of thing really isn’t done, but she did it anyway. With 150 miles behind her, she'd go on to travel nearly 100 miles more. She was different. She was Deer No. 255 and she was at the center of the University of Wyoming’s most recent deer-migration study.

Like the rest of her Wyoming-based herd, she followed the spring green-up across the Green River Basin. This area is desert, but as the weather warms, the river gives life to a vibrant line of vegetation that cuts across the otherwise dusty landscape. These herds are willing to migrate as far away as 150 miles. We know this thanks to the work of wildlife biologist Hall Sawyer, who originally documented Wyoming's Sublette herd’s record-setting journey in 2013.

Usually the 150-mile migration goes something like this:

A small herd, around 500 or so deer, travel 50 miles across the desert to a mountain range in western Wyoming known as the Wind River Range. There they merge with 4,000 to 5,000 more deer that spend winters in these Wind River foothills. By now thousands of mule deer are banded together like bangle-wearing gypsies pitching tents and singing songs. Next, they follow a narrow corridor along the base of the mountains for another 60 miles.

On this most-recently studied migration, Deer No. 255 followed this route. She had wintered near Superior, Wyoming, and migrated out with the others, made it to the mountain range and crossed the aforementioned 60-mile narrow corridor, which led her and thousands more to an area where they would cross the Green River Basin. Once on the other side, the herds traveled another 30 to 50 miles before they entered their summer range, Hoback Basin. When they arrived, Deer No. 255 was among them. Like the others, she’d just traveled the longest migration corridor ever documented for mule deer: 150 miles.

But unlike the others, she kept going.

“We had those deer that went to the Hoback, which we thought were pretty impressive,” says project collaborator Mark Zornes with the Wyoming Game and Fish Department, “and then this girl basically didn’t stop walking.”

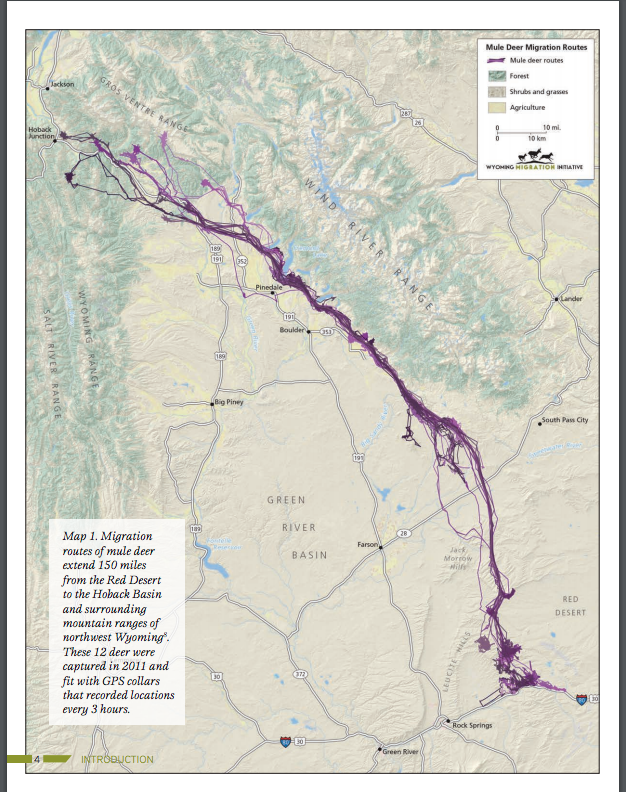

Migration routes of mule deer extend 150 miles from the Red Desert to the Hoback Basin and surrounding mountain ranges of northwest Wyoming . This map traces the paths of 12 deer moving along the corridor. The deer were captured in 2011 and fit with GPS collars that recorded locations every three hours. Credit: Wyoming Migration Initiative

Of all Wyoming ungulates, mule deer have the highest fidelity to their migration corridors. Put another way, they’re loyal to their well-worn paths. Yet such rare departures, as the University of Wyoming reports in its study, do happen. If you think about it from a human perspective, you might wonder if maybe this loner felt bored from a long winter spent in Superior, Wyoming and the 150-mile journey wasn’t enough to ease her restlessness. After all, the town of Superior only has 336 citizens according to its last census, so there’s not a ton going on there.

But mule deer are primal, like all wild animals, and restlessness and lonesomeness don't factor in like food, shelter and safety. And that's what makes Deer No. 255's will to continue on so fascinating and inexplicable. Because Hoback Basin is a nice place for summer — it's an ideal habitat. There, her needs would be met.

Wyoming mule deer prefer habitat with steep and rugged topography. They seek out rocky outcrops, a view of surrounding terrain and easy access to escape routes. Well, Hoback Basin gives you Hoback Formation, full of preserved fossils and rocky outcrops. This area should have been well suited for Deer No. 255. And during summer, mule deer prefer forbs over grasses, because the grass tends to dry out and cure in the summer heat. Guess what’s abundant in the mountain meadows of Hoback Basin? That’s right! Forbs.

The Hoback Basin is characterized by timbered draws, aspen stands, sagebrush slopes, riparian draws and mountain meadows, bounded by the high-elevation peaks of the Wyoming Range to the west and Gros Ventre Range to north and east. Credit: Wyoming Migration Initiative

But it didn’t matter, Deer No. 255 pressed on anyway. She circled the western edge of the Gros Ventre Range before one of her GPS fixes located her three-quarters of a mile from the entrance to Jackson Lake Lodge, a 385-room resort with 60-foot windows along the entire lobby and a panoramic view of Jackson Lake and the Grand Teton range. There were no reports that No. 255 inquired about vacancies or stopped in to try the tapas at the lodge’s Blue Heron restaurant.

She ended up, finally, in Idaho’s Island Park, arriving to her summer range on June 15. This was a journey Deer No. 255 began on March 20. It was a nice place — she stood among two-square-miles of meadows, wetlands and lodgepole pine. Yet, as biologists from the study report, it's not much to write home about. Certainly not the kind of habitat utopia you might imagine would warrant all those extra miles.

This gal, ol' 255, had just covered more documented ground during a spring migration than any other mule deer: an incredible 242 miles. For context, this is nowhere near the 15,248 miles Forrest Gump traveled in the epic film named after its protagonist. But that was only fiction and, anyways, this 242-mile trek is the longest recorded migration among any North American ungulates, topping the previous record of 150 miles. Only the caribou migrates farther. (The summer and winter ranges of the Porcupine caribou herd are about 400 miles apart.)

Of course, the story doesn’t end there.

The next step remains; the plan was to watch and see if Deer No. 255 would repeat this same journey to Idaho again the following spring, but in 2017, her GPS collar malfunctioned and she disappeared. This led to no contact until March 2018, when the study’s capture crew members spotted her near Superior, where they’d first found her on winter range two years before.

According to the study report, biologists still need to collect another year of movement data and will be watching closely this spring to see if Deer No. 255 makes the same incredible migration from near Wyoming's Interstate 80 to the far side of the Tetons.

“This is just one deer, but it shows the connectivity of this landscape in a way that exceeds our imaginations,” says U.S. Geological Survey wildlife biologist Matthew Kauffman, who directs the Wyoming Coop Unit and the Wyoming Migration Initiative. “That this mule deer herd in the Red Desert has persisted in making these epic migrations is a testament to their tenacity and the biological importance of migration.”

Watch how wildlife biologists, capture crews and the team at the University of Wyoming are capturing mule deer by helicopter to learn exactly where they go, what they eat and how healthy they are.

What's new in Field Guide to Hunting

How fast can turkeys fly?

Pathogen M.ovi confirmed for first time in Alaska Dall's sheep and mountain goats

How to make a European mount

Most weird deer antlers are not caused by genetics