Arguably the only thing worse than tuning a bow is retuning a bow. Tuning a bow to perfection can be a frustrating and time-consuming process, and all too often by next season—sometimes by next month—the bow has gone out of tune.

Arguably the only thing worse than tuning a bow is retuning a bow. Tuning a bow to perfection can be a frustrating and time-consuming process, and all too often by next season—sometimes by next month—the bow has gone out of tune.

So much do most bowhunters hate to tune bows that, when the first modern single-cams came along—offering the benefit of eliminating timing problems— bowhunters jumped on them so fast they revolutionized the bowhunting industry. It was the elimination of timing, or the need to synchronize the rollover of two cams, that drew many bowhunters to single-cam bows.

That is no small factor. Timing is critical to tuning two-cam bows, and even with modern, low-stretch strings, two cams are prone to go out of synch now and then, requiring that the bow be retuned. Single-cam bows, once tuned, tend to stay in tune longer.

Timing & Orientation

The single-cam design may eliminate the timing factor in tuning and may decrease the frequency with which a bow must be retuned, but to the extent a single-cam bow follows the modern trends toward faster, lighter, and shorter, tuning a single-cam bow can still be a challenge. And single-cam bows come with their very own tuning considerations.

Let’s start with timing. Some experts insist that timing is still a consideration, even for single-cam bows. True or not? Well, that depends on how you define “timing.” Better terms might be “synchronization,” in the case of two-cam bows, and “orientation” in the case of single-cams. The two cams of a two-cam bow must turn over at precisely the same time, which is to say they must be synchronized.

Obviously, this does not apply to the single-cam bow. Nonetheless, the single-cam must be positioned correctly relative to the string and cables—it must be properly oriented if the bow is to draw and shoot smoothly and achieve top efficiency. Sometimes the cam is not perfectly oriented out of the box. Even if it is, though, the string stretches over time, changing orientation of the cam and eventually causing the bow to go out of tune.

The change is usually gradual and not always immediately noticed, but over time the draw weight changes, the draw length changes, arrow speed is affected, nock travel is affected, the bow doesn’t shoot smoothly, and hand shock, recoil, and even noise levels can increase. If nothing else, peep sights and nock points move higher.

In some cases the change can be dramatic—the once-hard wall becomes a longer and softer valley, and the anchor point begins to vary, resulting in inconsistent arrow speeds and erratic shooting.

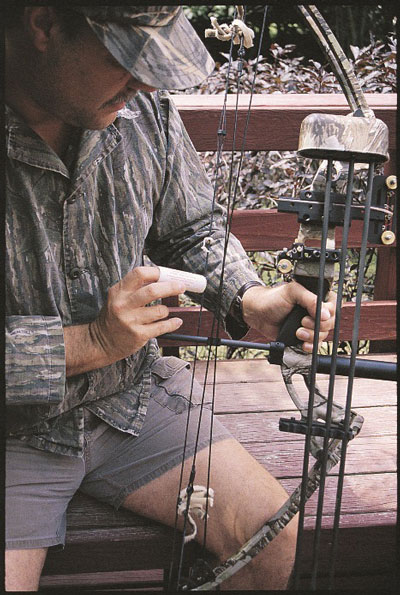

Many bowmakers design cams with tuning marks, so that orientation can be checked at a glance. Tuning marks have varied. One manufacturer employs two tiny holes for aligning parallel to the bowstring for optimum performance. For another, parallel lines are machined into other single-cams at the point where the power cable leaves the cam. If the cable doesn’t fit perfectly between the lines, the cam is not properly positioned.

Strings

So you really hate tuning bows, and that’s the main reason you bought a single-cam model. But do you really, really hate to tune bows? In that case, get an extremely low-stretch string. Modern strings are superior in this regard to anything available a few years ago, and most quality bows come out of the box with pretty good strings. To go one step better, shoot in the factory strings (at least 25 shots, but 100 shots is better), take them off to save as back-ups, and replace them with custom strings from a good custom string maker that offers top quality, pre-stretched strings/cables

By the way, you might not think of waxing your string as part of the tuning process, but strings that are unwaxed will become saturated with moisture from rain or dew, and moist strings tend to stretch. Beyond that, soak and then dry out bow strings a few times and their lives will be significantly shortened. When the string must be changed, guess what? It’s tuning time.

Draw Length

Most bowhunters are shooting at excessive draw lengths, but single-cam bows can magnify this problem in a couple of ways. First, draw length may be adjusted by only small amounts in the case of many single-cam bows. Some bow-makers argue that draw length for a given cam is critical, and that varying from that length by more than a small amount greatly affects performance. I’ll leave that debate to the engineers. Suffice it to say that if you select a single-cam bow with minimal adjustability, it is critical that you not choose a bow with a too-long draw length; you won’t have the option of changing it later.

Ever pick up an unfamiliar bow—perhaps one with a higher letoff than you are accustomed to—and unintentionally dry-fire it when the string creeps forward out of the valley and the cam grabs it unexpectedly? The draw cycle on single-cam bows is typically not as smooth as that of the better two-cam bows, pronouncing this effect. At proper draw weight and length, this is something you’ll soon become accustomed to and probably won’t notice. And, on the plus side, single-cam designs tend to feature a hard wall at the end of the draw, which most bowhunters prefer. At a draw length that is a little too long, though, the wall is hard to reach, or at least hard to maintain. The anchor point is not as consistent, the arm fatigues quickly, and the resulting string creep affects accuracy. Most bowhunters will shoot more comfortably, and more accurately, at shorter draw lengths.

Next: Rests, Dampening Devices, Shooting Form