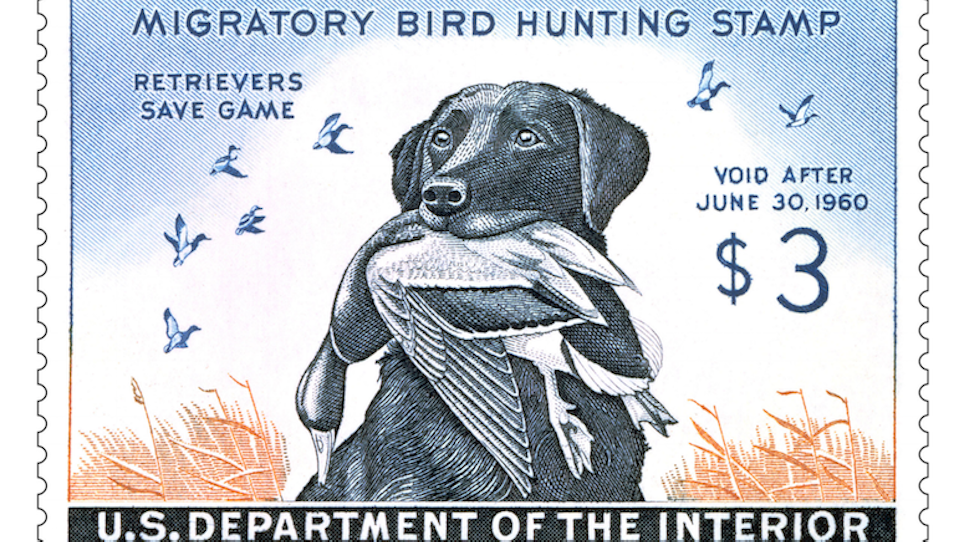

King Buck, a black Labrador retriever, was the only dog ever featured on a federal duck stamp. He appeared on the 1959 stamp in a watercolor painting by Maynard Reece, the most prolific duck-stamp artist of all time. This is Buck’s story.

In 1959, Reece learned officials with the Federal Duck Stamp Competition were encouraging artists to enter designs featuring a retrieving dog. The government felt this would emphasize the dog’s role in retrieving wounded or dead ducks that would otherwise be lost.

It had been eight years since Reece won his second duck-stamp competition. He wanted to try again. While doing research, he stopped at Nilo Kennels near Brighton, IL, and there he found the ideal subject — a retired hunting dog named King Buck.

King Buck was born with seven littermates in Iowa on April 3, 1948. All the pups were sold that fall, with one male going to Robert Howard of Omaha, Iowa, for $50. Unfortunately, the pup caught distemper. Howard took it into his home and placed it in a basket by a furnace.

The little retriever showed no improvement. Howard was advised to put him down. For a month, the pup was too sick to stand. No one understood how he managed to live.

Mrs. Howard tended to the puppy, and her loving attention finally turned the battle.

“One night, I went downstairs to have a look at him,” Robert Howard said, “And he managed to stand in his basket and greet me. I knew he was going to make it.”

Acting on the optimistic hunch that the convalescing puppy might someday rank high in his class, Howard named him “King Buck.” At the time, it was a hopeful idea. No one knew it was a prophecy.

The making of a king

When he reached 18 months, Buck began his first real field hunting. He tallied some impressive early victories in field trials, but still lacked a champion’s polish. He marked so poorly at times, Howard suspected bad eyesight caused by the distemper. But Buck continued improving and placed in several more derbies.

Howard sold Buck to Byron “Bing” Grunwald of Omaha for $500 in December 1949. He said it was growing knowledge of Buck’s potential that caused him to sell because he couldn’t afford to run the dog in top-flight trials and give Buck a real chance to prove himself. Before he was 2 years old, King Buck had won a first, two seconds and several third places in various Midwestern field trials. He still had wild days, however. Just after his third birthday, for example, Buck was running an open all-age stake at Lincoln, Nebraska. A triple-mark retrieve was set up, and Buck tore over most of the field for each bird picked up. After the trial, a judge told Howard, “That dog is nothing but a runner and will never amount to anything. If you’re smart, you’ll get rid of him.”

Two weeks after that trial, Buck won the open at Eagle, Wisconsin, displaying a breathtaking ability to “take a line.” One well-known trainer later remarked that if King Buck had “taken a line” to England, the Atlantic cable could have been laid along his course.That sterling bit of advice plagued the judge ever after. It’s doubtful some dog men in the Corn Belt circuit ever will forget it.

Buck’s instinct for retrieving soon caught the eye of John Olin, developer of Winchester’s Super-X Shotshell and founder of Nilo Farms and Kennels in Brighton, Illinois. Olin was dedicated to the sport of duck hunting and was looking for good retrievers to stock his new kennel.

Famous trainer Cotton Pershall sending King Buck to a fallen bird. Pershall worked tirelessly to develop strong assests in Buck, like the dogs ability to “take a line” without wavering.

Grunwald already had refused several offers for Buck, including one for $5,000, quite an appreciation from the $50 paid for an ailing pup. But when Olin topped the top offer by a satisfactory amount, Grunwald accepted. In June 1951, the dog was delivered to T.W. “Cotton” Pershall, the manager of Nilo Kennels.

The dog had an uncanny insight into competition, as Pershall described:

“He seemed to have some power of knowing when the competition was really rough, and he always came through. He wasn’t a big Lab, but he had great style. Always quiet and well-behaved, not excitable nor flashy. He just went steadily ahead with his job, series after series, whether on land or water.”

Under Cotton’s expert hand, the maturing King Buck realized his potential. In spring 1951, the Lab won a first, two seconds and a third. That fall, he took another first, a third and a fourth, and he completed 10 of 11 series of the 1951 National Championship Stake, placing high among the nation’s top retrievers. He made a slow start in 1952 with a first and a third in spring. In autumn, however, he won a first, second and a fourth.

In November 1952, Buck was entered in the “National” at Weldon Springs, Missouri. And, as always, Buck bore down when it counted. He obeyed superbly, responded sharply to commands and made direct, perfect retrieves. Right down to the final test, when he completed the 10th series with a 225-yard water retrieve, he performed like a champion. He had never been sharper.

At the beginning of the trial, King Buck had just been another dog in the pack. Three days later, he was officially the best retriever in the nation.

Related: Hunting Diving Ducks

A champion retriever

Soon after the trophy was awarded, Olin and his dog left the well-wishers and headed for Arkansas. Olin wanted to see if Buck could perform as well in flooded timber as he did in front of a gallery. As it turned out, the dog could and did.

When Olin and his dog arrived in Stuttgart, “The Duck Hunting Capital of The World,” the National Duck Calling Championship was just ending. Buck received a booming ovation by hundreds of the nation’s finest waterfowlers when he was introduced as the new national champion.

John Olin walked into Stuttgart’s Riceland Hotel that evening with Buck at heel. Buck was the center of attention and was offered champagne in his silver trophy bowl. A champion athlete in training, he sensibly abstained. Olin poured out the champagne and filled the bowl with water, and after Buck had quenched his thirst, the bowl was refilled with champagne and passed through the guests as a communal toast to the great dog.

King Buck and John Olin with some of the Lab’s many trophies.

One man refused the toast, saying “I’ll not drink from that bowl after a dog has used it!” At that time and place, the remark showed a signal lack of discretion. Under Olin’s withering glare, the guest was asked to leave the festivities and seek more antiseptic surroundings. For a moment, there was a possibility he might find such a germ-free climate in the local emergency ward.

The next day, Buck was taken to flooded timber for his first adventure with wild ducks, and he came typically to life. The ducks were plentiful and working well. King Buck was the only dog in the party, and he did all the retrieving for several gunners. He handled the wild mallards as efficiently and cleanly as field-trial birds, responding sharply to commands and taking obvious pleasure in his work.

Of King Buck, Olin said: “He was one of the finest wild duck retrievers I have ever seen. In spite of his intense field trial training, he loved natural hunting. He used his head in the wild, just as in field trials. That first wild duck shoot was his day — every minute of it — and he made the most of it. He was beautiful to watch.”

That night, Buck didn’t sleep on the floor of Olin’s hotel room; he jumped up on the foot of his master’s bed and spent the night in style. And it’s said that during the long years of field-trial campaigns, whenever Buck and Olin were on the road together, it was always the same. Where the master slept, the dog slept. During the drive to Stuttgart, as Buck lay on the front seat beside Olin, the tired dog rested his dog his head on his master’s leg — the first real affection he ever showed toward the man. It was that moment, after Buck’s first duck hunt, that sealed a bond between Olin and King Buck.

Related: Keep your dog healthy — the post-hunt checkup

Good dog

King Buck was an extraordinary retriever, always showing championship form, whether hunting mallards in flooded timber or birds under field-trial guns.

A steady performance won King Buck the title of the nation’s finest field-trial retriever again in 1953. He remained active in field trials for four years after that, still competing fiercely with younger dogs and established champions. As late as 1957, when he was 9 years old, he not only qualified for the National Championship Stake, but also completed 11 series out of 12 in the National and nearly won another title. During his years, he finished 83 national series out of a possible 85. To this day, no other retriever has ever completed more than 62 successive national series.

King Buck’s royal name was finally given its due in 1959. That year, the federal duck stamp commemorated the work of retrievers and their contribution to waterfowl conservation. And Maynard Reece, the famous Iowa wildlife artist whose work had already appeared on two duck stamps, came to Nilo and painted a watercolor portrait of perhaps the greatest duck dog of them all: King Buck. That was the winning entry. The 1959 duck stamp was a painting of old Buck with a mallard drake in his mouth, set against a backdrop of flaring ducks. It was the first time a dog ever appeared on a United States stamp.

Whitening about the muzzle, King Buck ruled Nilo Kennels for over a decade. In good weather, he sunned himself on the lawn or walked with slow dignity through the big exercise yard with other dogs racing about him.

When Buck was almost 14 years old, his health began failing. He died on March 28, 1962, and was interred in a small crypt near the entrance of his home at Nilo Kennels. A statue of him stands over his grave, a monument to one of the greatest duck dogs that ever lived.

Featured photo: The 1959 federal duck stamp by artist Maynard Reece, featuring King Buck of Nilo Kennels. Credit: The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service.